This etext was produced from Astounding Stories January 1931.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S.

copyright on this publication was renewed.

Astounding Stories

On Sale the First Thursday of Each Month

W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher

HARRY BATES, Editor

DR. DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor

The Clayton Standard on a Magazine Guarantees:

- That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid, by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors’ League of America;

- That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

- That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

- That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS

MONTHLY, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE,

WESTERN ADVENTURES, and WESTERN LOVE STORIES.

More Than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

| VOL. V, No. 1 | CONTENTS | JANUARY, 1931 |

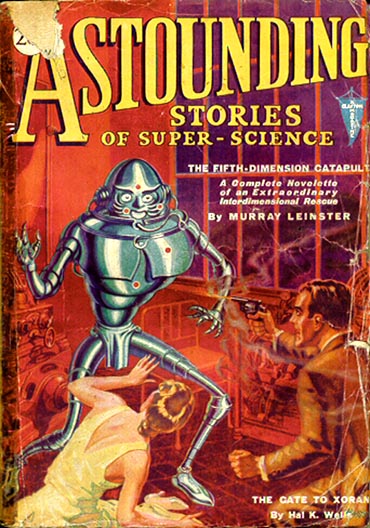

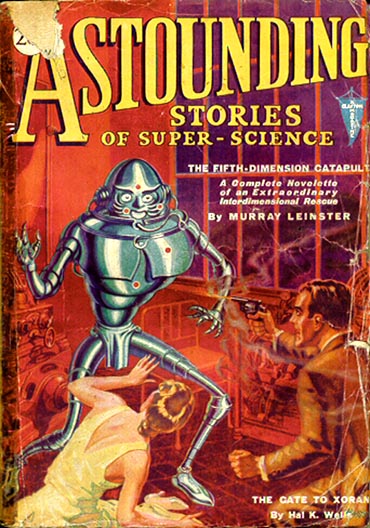

| COVER DESIGN | H. W. WESSO | |

| Painted in Water-Colors from a Scene in “The Gate to Xoran.” |

| THE DARK SIDE OF ANTRI | SEWELL PEASLEE WRIGHT | 9 |

| Commander John Hanson Relates an Interplanetary Adventure Illustrating the Splendid Service Spirit of the Men of the Special Patrol. |

| THE SUNKEN EMPIRE | H. THOMPSON RICH | 24 |

| Concerning the Strange Adventures of Professor Stevens with the Antillians on the Floor of the Mysterious Sargasso Sea. |

| THE GATE TO XORAN | HAL K. WELLS | 46 |

| A Strange Man of Metal Comes to Earth on a Dreadful Mission. |

| THE EYE OF ALLAH | C. D. WILLARD | 58 |

| On the Fatal Seventh of September a Certain Secret Service Man Sat in the President’s Chair and—Looked Back into the Eye of Allah. |

| THE FIFTH-DIMENSION CATAPULT | MURRAY LEINSTER | 72 |

| The Story of Tommy Reames’ Extraordinary Rescue of Professor Denham and his Daughter—Marooned in the Fifth Dimension. (A Complete Novelette.) |

| THE PIRATE PLANET | CHARLES W. DIFFIN | 109 |

| Two Fighting Yankees—War-Torn Earth’s Sole Representatives on Venus—Set Out to Spike the Greatest Gun of All Time. (Part Three of a Four-Part Novel.) |

| THE READERS’ CORNER | ALL OF US | 132 |

| A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding Stories. |

Single Copies, 20 Cents (In Canada, 25 Cents)

Yearly Subscription, $2.00

Issued monthly by Readers’ Guild, Inc., 80 Lafayette Street, New York, N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President;

Francis P. Pace, Secretary. Entered as second-class matter December 7, 1929, at the Post Office at

New York, N. Y., under Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered as a Trade Mark in the U. S. Patent Office.

Member Newsstand Group—Men’s List. For advertising rates address E. R. Crowe & Co., Inc., 25 Vanderbilt

Ave., New York; or 225 North Michigan Ave., Chicago.

“Behold one of those who live in the darkness.”

The Dark Side of Antri

By Sewell Peaslee Wright

Commander John Hanson relates an interplanetary

adventure illustrating the splendid

Service spirit of the men of the

Special Patrol.

An officer of the Special Patrol

Service dropped in to see me

the other day. He was a young

fellow, very sure of himself,

and very kindly towards an old man.

He was doing a

monograph, he

said, for his own

amusement, upon

the early forms

of our present offensive and defensive

weapons. Could I tell him about the

first Deuber spheres and the earlier

disintegrator rays and the crude atomic

bombs we tried back when I first

entered the Service?

I could, of

course. And I

did. But a man’s

memory does not improve in the

course of a century of Earth years.

Our scientists have not been able to

keep a man’s brain as fresh as his body,

despite all their vaunted progress.

There is a lot these deep thinkers, in

their great laboratories, don’t know.

The whole universe gives them the

credit for what’s been done, yet the

men of action who carried out the

ideas—but I’m getting away from my

pert young officer.

He listened to me with interest and

toleration. Now and then he helped

me out, when my memory failed me on

some little detail. He seemed to have

a very fair theoretical knowledge of

the subject.

“It seems impossible,” he commented,

when we had gone over the ground

he had outlined, “that the Service could

have done its work with such crude and

undeveloped weapons, does it not?” He

smiled in a superior sort of way, as

though to imply we had probably done

the best we could, under the circumstances.

I suppose I should not have permitted

his attitude to irritate me,

but I am an old man, and my life has

not been an easy one.

“Youngster,” I said—like many old

people, I prefer spoken conversation—“back

in those days the Service was

handicapped in every way. We lacked

weapons, we lacked instruments, we

lacked popular support, and backing.

But we had men, in those days, who

did their work with the tools that were

at hand. And we did it well.”

“Yes, sir!” the youngster said hastily—after

all, a retired commander in

the Special Patrol Service does rate a

certain amount of respect, even from

these perky youngsters—“I know that,

sir. It was the efforts of men like

yourself who gave us the proud traditions

we have to-day.”

“Well, that’s hardly true,” I corrected

him. “I’m not quite so old as

that. We had a fine set of traditions

when I entered the Service, son. But

we did our share to carry them on, I’ll

grant you that.”

“‘Nothing Less than Complete Success,’”

quoted the lad almost reverently,

giving the ancient motto of our service.

“That is a fine tradition for a

body of men to aspire to, sir.”

“True. True.” The ring in the boy’s

voice brought memories flocking. It

was a proud motto; as old as I am,

the words bring a thrill even now, a

thrill comparable only with that which

comes from seeing old Earth swell up

out of the darkness of space after days

of outer emptiness. Old Earth, with

her wispy white clouds and her broad

seas— Oh, I know I’m provincial, but

that is another thing that must be forgiven

an old man.

“I imagine, sir,” said the young

officer, “that you could tell many a

strange story of the Service, and the

sacrifices men have made to keep that

motto the proud boast it is to-day.”

“Yes,” I told him. “I could do that.

I have done so. That is my occupation,

now that I have been retired from

active service. I—”

“You are a historian?” he broke in

eagerly.

I forgave him the interruption.

I can still remember my own rather

impetuous youth.

“Do I look like a historian?” I think

I smiled as I asked him the question,

and held out my hands to him. Big

brown hands they are, hardened with

work, stained and drawn from old acid

burns, and the bite of blue electric

fire. In my day we worked with crude

tools indeed; tools that left their mark

upon the workman.

“No. But—”

I waved the explanation aside.

“Historians deal with facts, with accomplishments,

with dates and places

and the names of great men. I write—what

little I do write—of men and high

adventures, so that in this time of softness

and easy living some few who may

read my scribblings may live with me

those days when the worlds of the universe

were strange to each other, and

there were many new things to be

found and marveled at.”

“And I’ll venture, sir, that you find

much enjoyment in the work,” commented

the youngster with a degree of

perception with which I had not

credited him.

“True. As I write, forgotten faces

peer at me through the mists of the

years, and strong, friendly voices call

to me from out of the past….”

“It must be wonderful to live the

old adventures through again,” said the

young officer hastily. Youth is always

afraid of sentiment in old people. Why

this should be, I do not know. But it

is so.

The lad—I wish I had made a note

of his name; I predict a future for him

in the Service—left me alone, then,

with the thoughts he had stirred up in

my mind.

Old faces … old voices. Old

scenes, too.

Strange worlds, strange peoples. A

hundred, a thousand different tongues.

Men that came only to my knee, and

men that towered ten feet above my

head. Creatures—possessed of all the

attributes of men except physical form—that

belonged only in the nightmare

realms of sleep.

An old man’s most treasured possessions:

his memories. A face drew close

out of the flocking recollections; the

face of a man I had known and loved

more than a brother so many years—dear

God, how many years—ago.

Anderson Croy. Search all the voluminous

records of the bearded historians,

and you will not find his name.

No great figure of history was this

friend of mine; just an obscure officer

on an obscure ship of the Special Patrol

Service.

And yet there is a people who owe to

him their very existence.

I wonder if they have forgotten him?

It would not surprise me.

The memory of the universe is not a

reliable thing.

Anderson Croy was, like most

of the officer personnel of the

Special Patrol Service, a native of

Earth.

They had tried to make a stoop-shouldered

dabbler in formulas out of

him, but he was not the stuff from

which good scientists are moulded. He

was young, when I first knew him, and

strong; he had mild blue eyes and a

quick smile. And he had a fine, steely

courage that a man could love.

I was in command, then, of the Ertak,

my second ship. I inherited Anderson

Croy with the ship, and I liked him

from the first time I laid eyes upon

him.

As I recall it, we worked together

on the Ertak for nearly two years,

Earth time. We went through some

tight places together. I remember our

experience, shortly after I took over

the Ertak, on the monstrous planet

Callor, whose tiny, gentle people were

attacked by strange, vapid Things that

come down upon them from the fastness

of the polar cap, and—

But I wander from the story I wish

to tell here. An old man’s mind is

a weak and weary thing that totters and

weaves from side to side; like a worn-out

ship, it is hard to keep on a straight

course.

We were out on one of those long,

monotonous patrols, skirting the outer

boundaries of the known universe, that

were, at that time, before the building

of all the many stations we have to-day

a dreaded part of the Special Patrol

Service routine.

Not once had we landed to stretch

our legs. Slowing up to atmospheric

speed took time, and we were on a

schedule that allowed for no waste of

even minutes. We approached the various

worlds only close enough to report,

and to receive an assurance that all was

well. A dog’s life, but part of the

game.

My log showed nearly a hundred

“All’s well” reports, as I remember

it, when we slid up to Antri, which

was, so far as size is concerned, one of

our smallest ports o’ call.

Antri, I might add, for the benefit of

those who have forgotten their maps of

the universe, is a satellite of A-411,

which, in turn, is one of the largest

bodies of the universe, and both uninhabited

and uninhabitable. Antri is

somewhat larger than the moon, Earth’s

satellite, and considerably farther from

its controlling body.

“Report our presence, Mr. Croy,” I

ordered wearily. “And please ask Mr.

Correy to keep a sharp watch on the

attraction meter.” These huge bodies

such as A-411 are not pleasant companions

at space speeds. A few minute’s

trouble—space ships gave trouble,

in those days—and you melted like a

drop of solder when you struck the

atmospheric belt.

“Yes, sir!” There never was a crisper

young officer than Croy.

I bent over my tables, working out

our position and charting our course

for the next period. In a few seconds

Croy was back, his blue eyes gleaming.

“Sir, an emergency is reported on

Antri. We are to make all possible

speed, to Oreo, their governing city. I

gather that it is very important.”

“Very well, Mr. Croy.” I can’t say

the news was unwelcome. Monotony

kills young men. “Have the disintegrator

ray generators inspected and tested.

Turn out the watch below in such time

that we may have all hands on duty

when we arrive. If there is an emergency,

we shall be prepared for it. I

shall be with Mr. Correy in the navigating

room; if there are any further

communications, relay them to me

there.”

I hurried up to the navigating

room, and gave Correy his orders.

“Do not reduce speed until it is absolutely

necessary,” I concluded. “We

have an emergency call from Antri,

and minutes may be important. How

long do you make it to Oreo?”

“About an hour to the atmosphere;

say an hour more to set down in the

city. I believe that’s about right, sir.”

I nodded, frowning at the twin

charts, with their softly glowing lights,

and turned to the television disc, picking

up Antri without difficulty.

Of course, back in those days we

had the huge and cumbersome discs,

their faces shielded by a hood, that

would be suitable only for museum

pieces now. But they did their work

very well, and I searched Antri carefully,

at varying ranges, for any sign

of disturbances. I found none.

The dark portion, of course, I could

not penetrate. Antri has one portion

of its face that is turned forever from

its sun, and one half that is bathed in

perpetual light. The long twilight

zone was uninhabited, for the people

of Antri are a sun-loving race, and

their cities and villages appeared only

in the bright areas of perpetual sunlight.

Just as we reduced to atmospheric

speed, Croy sent up a message

“The Governing Council sends word

that we are to set down on the platform

atop the Hall of Government,

the large, square white building in the

center of the city. They say we will

have no difficulty in locating it.”

I thanked him and ordered him to

stand by for further messages, if any,

and picked up the far-flung city of

Oreo in my television disc.

There was no mistaking the

building Croy had mentioned. It

stood out from the city around it, cool

and white, its mighty columns glistening

like crystal in the sun. I could

even make out the landing platform,

slightly elevated above the roof on

spidery arches of silvery metal.

We sped straight for the city at just

a fraction of space speed, but the

hand of the surface temperature gauge

crept slowly toward the red line that

marked the dangerous incandescent

point. I saw that Correy, like the good

navigating officer he was, was watching

the gauge as closely as myself, and

hence said nothing. We both knew that

the Antrians would not have sent a

call for help to a ship of the Special

Patrol Service if there had not been

a real emergency.

Correy had made a good guess in

saying that it would take about an

hour, after entering the gaseous envelope

of Antri, to reach our destination.

It was just a few minutes—Earth time,

of course—less than that when we settled

gently onto the landing platform.

A group of six or seven Antrians,

dignified old men, wearing the short,

loosely belted white robes that we

found were their universal costume,

were waiting for us at the exit of the

Ertak, whose sleek, smooth sides were

glowing dull red.

“You have hastened, and that is well,

sirs,” said the spokesman of the committee.

“You find Antri in dire need.”

He spoke in the universal language,

and spoke it softly and perfectly. “But

you will pardon me for greeting you

with that which is, of necessity, uppermost

in my mind, and in the minds of

these, my companions.

“Permit me to welcome you to Antri,

and to introduce those who extend

those greetings.” Rapidly, he ran

through a list of names, and each of

the men bowed gravely in acknowledgment

of our greetings. I have never

observed a more courteous nor a more

courtly people than the Antrians; their

manners are as beautiful as their faces.

Last of all, their spokesman introduced

himself. Bori Tulber, he was

called, and he had the honor of being

master of the Council—the chief executive

of Antri.

When the introductions had

been completed, the committee

led our little party to a small, cylindrical

elevator which dropped us,

swiftly and silently, on a cushion of

air, to the street level of the great

building. Across a wide, gleaming corridor

our conductors led us, and stood

aside before a massive portal through

which ten men might have walked

abreast.

We found ourselves in a great

chamber with a vaulted ceiling of

bright, gleaming metal. At the far end

of the room was an elevated rostrum,

flanked on either side by huge, intricate

masses of statuary, of some

creamy, translucent stone that glowed

as with some inner light. Semicircular

rows of seats, each with its carved

desk, surmounted by numerous electrical

controls, occupied all the floor

space. None of the seats was occupied.

“We have excused the Council from

our preliminary deliberations,” explained

Bori Tulber, “because such a

large body is unwieldy. My companions

and myself represent the executive

heads of the various departments of the

Council, and we are empowered to act.”

He led us through the great council

chamber, and into an anteroom, beautifully

decorated, and furnished with

exceedingly comfortable chairs.

“Be seated, sirs,” the Master of the

Council suggested. We obeyed silently,

and Bori Tulber stood before, gazing

thoughtfully into space.

“I do not know just where to begin,”

he said slowly. “You men

in uniform know, I presume, but little

of this world of ours. I presume I had

best begin far back.

“Since you are navigators of space,

undoubtedly, you are acquainted with

the fact that Antri is a world divided

into two parts; one of perpetual night,

and the other of perpetual day, due to

the fact that Antri revolves but once

upon its axis during the course of its

circuit of its sun, thus presenting always

the same face to our luminary.

“We have no day and night, such as

obtain on other spheres. There are no

set hours for working nor for sleeping

nor for pleasure. The measure of a

man’s work is the measure of his ambition,

or his strength, or his desire.

It is so also with his sleep and with

his pleasures. It is—it has been—a

very pleasant arrangement.

“Ours is a fertile country, and our

people live very long and very happily

with little effort. We have believed

that ours was the nearest of all the

worlds to the ideal; that nothing could

disturb the peace and happiness of our

people. We were mistaken.

“There is a dark side to Antri.

A side upon which the sun never

has shone. A dismal place of gloom,

which is like the night upon other

worlds.

“No Antrian has, to our knowledge,

ever penetrated this part of Antri, and

lived to tell of his experience. We do

not even till the land close to the twilight

zone. Why should we, when we

have so much fine land upon which the

sun shines bright and fair always, save

for the two brief seasons of rain?

“We have never given thought to

what might be on the dark face of Antri.

Darkness and night are things unknown

to us; we know of them only

from the knowledge which has come to

us from other worlds. And now—now

we have been brought face to face with

a terrible danger which comes to us

from that other side of this sphere.

“A people have grown there. A terrible

people that I shall not try to describe

to you. They threaten us with

slavery, with extinction. Four ara ago

(the Antrians have their own system

of reckoning time, just as we have on

Earth, instead of using the universal

system, based upon the enaro. An ara

corresponds to about fifty hours, Earth

time.) we did not know that such a

people existed. Now their shadow is

upon all our beautifully sunny country,

and unless you can aid us, before

other help can reach us, I am convinced

that Antri is doomed!”

For a moment not one of us spoke.

We sat there, staring at the old

man who had just ceased speaking.

Only a man ripened and seasoned

with the passing of years could have

stood there before us and uttered, so

quietly and solemnly, words such as

had just come from his lips. Only in

his eyes could we catch a glimpse of

the torment which gripped his soul.

“Sir,” I said, and have never felt

younger than at that moment, when

I tried to frame some assurance to this

splendid old man who had turned to

me and my youthful crew for succor,

“we shall do what it lies within our

power to do. But tell us more of this

danger which threatens.

“I am no man of science, and yet I

cannot see how men could live in a

land never reached by the sun. There

would be no heat, no vegetation. Is

that not so?”

“Would that it were!” replied the

Master of the Council, bitterly. “What

you say would be indeed the truth,

were it not for the great river and

seas of our sunny Antri, which bear

their heated waters to this dark portion

of our world, and make it habitable.

“And as for this danger, there is

little to be said. At some time, men

of our country, men who fish, or venture

upon the water in commerce, have

been borne, all unwillingly, across the

shadowy twilight zone and into the

land of darkness. They did not come

back, but they were found there and

despoiled of their menores.

“Somehow, these creatures who dwell

in darkness determined the use of the

menore, and now that they have resolved

that they shall rule all this

sphere, they have been able to make

their threat clear to us. Perhaps”—and

Bori Tulber smiled faintly and terribly—“you

would like to have that

message direct from its bearer?”

“Is that possible, sir?” I asked eagerly,

glancing around the room.

“How—”

“Come with me,” said the Master of

the Council gently. “Alone—for too

many near him excites this terrible

messenger. You have your menore?”

“No. I had not thought there would

be need of it.” The menores of those

days, it should be remembered, were

heavy, cumbersome circlets that were

worn upon the head like a sort of

crown, and one did not go so equipped

unless in real need of the device. To-day,

of course, your menores are but

jeweled trinkets that convey thought a

score of times more effectively, and

weigh but a tenth as much.

“It is a lack easily remedied.” Bori

Tulber excused himself with a little

bow and hurried out into the great

council chamber, to appear again in a

moment with a menore in either hand.

“Now, if your companions and mine

will excuse us for a moment….” He

smiled around the seated group apologetically.

There was a murmur of assent,

and the old man opened a door

in the other side of the room.

“It is not far,” he said. “I will go

first, and show you the way.”

He led me quickly down a long,

narrow corridor to a pair of steep

stairs that circled far down into the

very foundation of the building. The

walls of the corridor and the stairs

were without windows, but were as

bright as noonday from the ethon tubes

which were set into both ceiling and

walls.

Silently we circled our way down the

spiral stairs, and silently the Master of

the Council paused before a door at the

bottom—a door of dull red metal.

“This is the keeping place of those

who come before the Council charged

with wrong doing,” explained Bori

Tulber. His fingers rested upon and

pressed certain of a ring of small white

buttons in the face of the door, and

it opened swiftly and noiselessly. We

entered, and the door closed behind us

with a soft thud.

“Behold one of those who live in the

darkness,” said the Master of the Council

grimly. “Do not put on the menore

until you have a grip upon yourself:

I would not have him know how greatly

he disturbs us.”

I nodded, dumbly, holding the heavy

menore dangling in my hand.

I have said that I have beheld strange

worlds and strange people in my life,

and it is true that I have. I have seen

the headless people of that red world

Iralo, the ant people, the dragon-fly

people, the terrible carnivorous trees

of L-472, and the pointed heads of a

people who live upon a world which

may not be named. But I have still

to see a more terrible creature than

that which lay before me now.

He—or it—was reclining upon the

floor, for the reason that he could

not have stood. No room save one with

a vaulted ceiling such as the great

council chamber, could offer room

enough for this creature to walk erect.

He was, roughly, a shade better than

twice my height, yet I believe he would

have weighed but little more. You have

seen rank weeds that have grown up

in the darkness to reach the sun; if

you can imagine a man who had done

likewise, you can, perhaps, picture that

which I saw before me.

His legs at the thigh were no larger

than my arm, and his arms were but

half the size of my wrist, and jointed

twice instead of but once. He wore a

careless garment of some dirty yellow,

shaggy hide, and his skin, revealed on

feet and arms and face, was a terrible,

bloodless white; the dead white of a

fish’s belly. Maggot white. The white

of something that had never known

the sun.

The head was small and round, with

features that were a caricature of

man’s. His ears were huge, and had the

power of movement, for they cocked

forward as we entered the room. The

nose was not prominently arched, but

the nostrils were wide, and very thin,

as was his mouth, which was faintly

tinged with dusky blue, instead of

healthy red. At one time his eyes had

been nearly round, and, in proportion,

very large. Now they were but shadowy

pockets, mercifully covered by

shrunken, wrinkled lids that twitched

but did not lift.

He moved as we entered, and from

a reclining position, propped up

on the double elbows of one spidery

arm, he changed to a sitting position

that brought his head nearly to the

ceiling. He smiled sickeningly, and

a queer, sibilant whispering came from

the bluish lips.

“That is his way of talking,” explained

Bori Tulber. “His eyes, you

will note, have been gouged out. They

cannot stand the light; they prepared

their messenger carefully for his work,

you’ll see.”

He placed his menore upon his head,

and motioned me to do likewise. The

creature searched the floor with one

white, leathery hand, and finally located

his menore, which he adjusted

clumsily.

“You will have to be very attentive,”

explained my companion. “He expresses

himself in terms of pictures

only, of course, and his is not a highly

developed mind. I shall try to get him

to go over the entire story for us again,

if I can make him understand. Emanate

nothing yourself; he is easily confused.”

I nodded silently, my eyes fixed with

a sort of fascination upon the creature

from the darkness, and waited.

Back on the Ertak again. I called

all my officers together for a conference.

“Gentlemen,” I said, “we are confronted

with a problem of such gravity

that I doubt my ability to describe it

clearly.

“Briefly, this civilized, beautiful portion

of Antri is menaced by a terrible

fate. In the dark portion of this unhappy

world there live a people who

have the lust of conquest in their hearts—and

the means at hand with which to

wreck this world of perpetual sunlight.

“I have the ultimatum of this people

direct from their messenger. They want

a terrible tribute in the form of slaves.

These slaves would have to live in perpetual

darkness, and wait upon the

whims of the most monstrous beings

these eyes of mine have ever seen.

And the number of slaves demanded

would—as nearly as I could gather,

mean about a third of the entire population.

Further tribute in the form of

sufficient food to support these slaves

is also demanded.”

“But, in God’s name, sir,” burst forth

Croy, his eyes blazing, “by what means

do they, propose to inforce their infamous

demands?”

“By the power of darkness—and a

terrible cataclysm. Their wise men—and

it would seem that some of them

are not unversed in science—have discovered

a way to unbalance this world,

so that they can cause darkness to creep

over this land that has never known it.

And as darkness advances, these people

of the sun will be utterly helpless before

a race that loves darkness, and can

see in it like cats. That, gentlemen, is

that fate which confronts this world of

Antri!”

There was a ghastly silence for a

moment, and then Croy, always

impetuous, spoke up again.

“How do they propose to do this

thing sir?”, he asked hoarsely.

“With devilish simplicity. They have

a great canal dug nearly to the great

polar cap of ice. Should they complete

it, the hot waters of their seas will be

liberated upon this vast ice field, and

the warm waters will melt it quickly.

If you have not forgotten your lessons,

gentlemen, you will remember, since

most of you are of Earth, that our

scientists tell us our own world turned

over in much this same fashion, from

natural means, and established for itself

new poles. Is that not true?”

Grave, almost frightened nods travelled

around the little semicircle of

white, thoughtful faces.

“And is there nothing, sir, that we

can do?” asked Kincaide, my second

officer, in an awed whisper.

“That is the purpose of this conclave:

to determine what may be done.

We have our bombs and our rays, it

is true, but what is the power of this

one ship against the people of half a

world? And such a people!” I shuddered,

despite myself, at the memory

of that grinning creature in the cell

far below the floor of the council chamber.

“This city, and its thousands, we

might save, it is true—but not the

whole half of this world. And that

is the task the Council and its Master

have set before us.”

“Would it be possible to

frighten them?” asked Croy.

“I gather that they are not an advanced

race. Perhaps a show of power—the

rays—the atomic pistol—bombs— Call

it strategy, sir, or just plain bluff. It

seems the only chance.”

“You have heard the suggestion, gentlemen,”

I said. “Has anyone a better?”

“How does Mr. Croy plan to frighten

these people of the darkness?” asked

Kincaide, who was always practical.

“By going to their country, in this

ship, and then letting events take their

course,” replied Croy promptly. “Details

will have to be settled on the spot,

as I see it.”

“I believe Mr. Croy is right,” I decided.

“The messenger of these people

must be returned to his own kind; the

sooner the better. He has given me a

mental map of his country; I believe

that it will be possible for me to locate

the principal city, in which his ruler

lives. We will take him there, and

then—may God aid us gentlemen.”

“Amen,” nodded Croy, and the echo

of the word ran from lip to lip like

the prayer it was. “When do we

start?”

I hesitated for just an instant.

“Now,” I brought forth crisply. “Immediately.

We are gambling with the

fate of a world, a fine and happy people.

Let us throw the dice quickly, for

the strain of waiting will not help us.

Is that as you would wish it, gentlemen?”

“It is, sir!” came the grave chorus.

“Very well. Mr. Croy, please report

with a detail of ten men, to Bori Tulber,

and tell him of our decision.

Bring the messenger back with you.

The rest of you, gentlemen, to your

stations. Make any preparations you

may think advisable. Be sure that every

available exterior light is in readiness.

Let me be notified the moment the messenger

is on board and we are ready to

take off. Thank you, gentlemen!”

I hastened to my quarters and

brought the Ertak’s log down to the

minute, explaining in detail the course

of action we had decided upon, and the

reasons for it. I knew, as did all the

Ertak’s officers who had saluted so

crisply, and so coolly gone about the

business of carrying out my orders,

that we would return from our trip

to the dark side of Antri triumphant

or—not at all.

Even in these soft days, men still

respect the stern, proud motto of our

service: “Nothing Less Than Complete

Success.” The Special Patrol does what

it is ordered to do, or no man returns

to present excuses. That is a tradition

to bring tears of pride to the eyes of

even an old man, in whose hands there

is strength only for the wielding of a

pen. And I was young, in those days.

It was perhaps a quarter of an hour

when word came from the navigating

room that the messenger was aboard,

and we were ready to depart. I closed

the log, wondering, I remember, if I

would ever make another entry therein,

and, if not, whether the words I had

just inscribed would ever see the light

of day. The love of life is strong in

men so young. Then I hurried to the

navigating room and took charge.

Bori Tulber had furnished me with

large scale maps of the daylight portion

of Antri. From the information

conveyed to me by the messenger of

the people of darkness—the Chisee

they called themselves, as nearly as I

could get the sound—I rapidly

sketched in the map of the other side

of Antri, locating their principal city

with a small black circle.

Realising that the location of the

city we sought was only approximate,

we did not bother to work out exact

bearings. We set the Ertak on her

course at a height of only a few thousand

feet, and set out at low atmospheric

speed, anxiously watching for

the dim line of shadow that marked

the twilight zone, and the beginning

of what promised to be the last mission

of the Ertak and every man she carried

within her smooth, gleaming body.

“Twilight zone in view, sir,”

reported Croy at length.

“Thank you, Mr. Croy. Have all the

exterior lights and searchlights turned

on. Speed and course as at present,

for the time being.”

I picked up the twilight zone without

difficulty in the television disc, and at

full power examined the terrain.

The rich crops that fairly burst from

the earth of the sunlit portion of Antri

were not to be observed here. The

Antrians made no effort to till this

ground, and I doubt that it would have

been profitable to do so, even had they

wished to come so close to the darkness

they hated.

The ground seemed dank, and great

dark slugs moved heavily upon its

greasy surface. Here and there strange

pale growths grew in patches—twisted,

spotted growths that seemed somehow

unhealthy and poisonous.

I searched the country ahead, pressing

further and further into the line

of darkness that was swiftly approaching.

As the light of the sun faded, our

monstrous searchlights cut into the

gloom ahead, their great beams slashing

the shadows.

In the dark country I had expected

to find little if any vegetable growth.

Instead, I found that it was a veritable

jungle through which even our searchlight

rays could not pass.

How tall the growths of this jungle

might be, I could not tell, yet I had

the feeling that they were tall indeed.

They were not trees, these pale, weedy

arms that reached towards the dark

sky. They were soft and pulpy, and

without leaves; just long naked sickly

arms that divided and subdivided and

ended in little smooth stumps like amputated

limbs.

That there was some kind of activity

within the shelter of this weird jungle,

was evident enough, for I could catch

glimpses, now and then of moving

things. But what they might be, even

the searching eye of the television disc

could not determine.

One of our searchlight beams, waving

through the darkness like the

curious antenna of some monstrous insect,

came to rest upon a spot far ahead.

I followed the beam with the disc, and

bent closer, to make sure my eyes did

not deceive me.

I was looking at a vast cleared place

in the pulpy jungle—a cleared space in

the center of which there was a city.

A city built of black, sweating stone,

each house exactly like every other

house: tall, thin slices of stone, without

windows, chimneys or ornamentation

of any kind. The only break in

the walls was the slit-like door of each

house. Instead of being arranged along

streets crossing each other at right

angles, these houses were built in concentric

circles broken only by four

narrow streets then ran from the open

space in the center of the city to the

four points of the compass. Around

the entire city was an exceedingly high

wall built of and buttressed with the

black, sweating stone of which the

houses were constructed.

That it was a densely populated city

there was ample evidence. People—they

were creatures like the messenger;

that the Chisee are a people, despite

their terrible shape, is hardly

debatable—were running up and down

the four radial streets, and around the

curved connecting streets, in the wildest

confusion, their double-elbowed

arms flung across their eyes. But even

as I watched, the crowd thinned and

melted swiftly away, until the streets

of the queer, circular city were utterly

deserted.

“The city ahead is not the one we

are seeking, sir?” asked Croy,

who had evidently been observing the

scene through one of the smaller television

discs. “I take it that governing

city will be farther in the interior.”

“According to my rather sketchy information,

yes.” I replied. “However,

keep all the searchlight operators busy,

going over very bit of the country

within the reach of their beams. You

have men on all the auxiliary television

discs?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good. Any findings of interest

should be reported to me instantly.

And—Mr. Croy!”

“Yes, sir?”

“You might order, if you will, that

rations be served all men at their

posts.” Over such country as this, I

felt it would be wise to have every

man ready for an emergency. It was,

perhaps, as well that I issued this order.

It was perhaps half an hour after we

had passed the circular city when, far

ahead, I could see the pale, unhealthy

forest thinning out. A half dozen of

our searchlight beams played upon the

denuded area, and as I brought the television

disc to bear I saw that we were

approaching a vast swamp, in which

little pools of black water reflected the

dazzling light of our searching beams.

Nor was this all. Out of the swamp

a thousand strange, winged things were

rising: yellowish, bat-like things with

forked tails and fierce hooked beaks.

And like some obscene miasma from

that swamp, they rose and came

straight for the Ertak!

Instantly I pressed the attention

signal that warned every man on

the ship.

“All disintegrator rays in action at

once!” I barked into the transmitter.

“Broad beams, and full energy. Bird-like

creatures, dead ahead; do not cease

action until ordered!”

I heard the disintegrator ray generators

deepen their notes before I finished

speaking, and I smiled grimly,

turning to Correy.

“Slow down as quickly and as much

as possible, Mr. Correy,” I ordered.

“We have work to do ahead.”

He nodded, and gave the order to

the operating room; I felt the forward

surge that told me my order was being

obeyed, and turned my attention again

to the television disc.

The ray operators were doing their

work well. The search lights showed

the air streaked with fine siftings of

greasy dust, and these strange winged

creatures were disappearing by the

scores as the disintegrator rays beat

and played upon them.

But they came on gamely, fiercely.

Where there had been thousands, there

were but hundreds … scores …

dozens….

There were only five left. Three of

them disappeared at once, but the two

remaining came on unhesitatingly,

their dirty yellow bat-like wings flapping

heavily, their naked heads outstretched,

and hooked beaks snapping.

One of them disappeared in a little

sifting of greasy dust, and the same

ray dissolved one wing of the remaining

creature. He turned over suddenly,

the one good wing flapping wildly, and

tumbled towards the waiting swamp

that has spawned him. Then, as the

ray eagerly followed him, the last of

that hellish brood disappeared.

“Circle slowly, Mr. Correy,” I ordered.

I wanted to make sure there

were none of these terrible creatures

left. I felt that nothing so terrible

should be left alive—even in a world

of darkness.

Through the television disc I

searched the swamp. As I had

half suspected, the filthy ooze held the

young of this race of things: grub-like

creatures that flipped their heavy

bodies about in the slime, alarmed by

the light which searched them out.

“All disintegrator rays on the

swamp,” I ordered. “Sweep it from

margin to margin. Let nothing be left

alive there.”

I had a well trained crew. The disintegrator

rays massed themselves into

a marching wall of death, and swept

up and down the swamp as a plough

turns its furrows.

It was easy to trace their passage,

for behind them the swamp disappeared,

leaving in its stead row after

row of broad, dusty paths. When we

had finished there was no swamp: there

was only a naked area upon which

nothing lived, and upon which, for

many years, nothing would grow.

“Good work,” I commended the disintegrator

ray men. “Cease action.”

And then, to Correy, “Put her on her

course again, please.”

An hour went by. We passed several

more of the strange, damp circular cities,

differing from the first we

had seen only in the matter of size.

Another hour passed, and I became

anxious. If we were on our proper

course, and I had understood the Chisee

messenger correctly, we should be

very close to the governing city. We

should—

The waving beam of one of the

searchlights came suddenly to rest.

Three or four other beams followed it—and

then all the others.

“Large city to port, sir!” called Croy

excitedly.

“Thank you. I believe it is our destination.

Cut all searchlights except

the forward beam. Mr. Correy!”

“Yes, sir.”

“You can take her over visually now,

I believe. The forward searchlight

beam will keep our destination in view

for you. Set her down cautiously in

the center of the city in any suitable

place. And—remain at the controls

ready for any orders, and have the

operating room crew do likewise.”

“Yes, sir,” said Correy crisply.

With a tenseness I could not control,

I bent over the hooded television disc

and studied the mighty governing city

of the Chisee.

The governing city of the Chisee

was not unlike the others we had

seen, save that it was very much larger,

and had eight spoke-like streets radiating

from its center, instead of four.

The protective wall was both thicker

and higher.

There was another difference. Instead

of a great open space in the center

of the city, there was a central,

park-like space, in the middle of which

was a massive pile, circular in shape,

and built, like all the rest of the city,

of the black, sweating rock which

seemed to be the sole building material

of the Chisee.

We set the Ertak down close to the

big circular building, which we guessed—and

correctly—to be the seat of government.

I ordered the searchlight ray

to be extinguished the moment we

landed, and the ethon tubes that illuminated

our ship inside to be turned

off, so that we might accustom our

eyes as much as possible to darkness,

finding our way about with small ethon

tube flashlights.

With a small guard, I stood at the

forward exit of the Ertak and watched

the huge circular door back out on its

mighty threads, and finally swing to

one side on its massive gimbals. Croy—the

only officer with me—and I both

wore our menores, and carried full

expeditionary equipment, as did the

guard.

The Chisee messenger, grimacing

and talking excitedly in his sibilant,

whispering voice, crouched on all fours

(he could not stand in that small space)

and waited, three men of the guard on

either side of him. I placed his menore

on his head and gave him simple, forceful

orders, picturing them for him as

best I could:

“Go from this place and find others

of your kind. Tell them that we would

speak to them with things such as you

have upon your head. Run swiftly!”

“I will run,” he conveyed to me, “to

those great ones who sent me.” He

pictured them fleetingly. They were

creatures like himself, save that they

were elaborately dressed in fine skins

of several pale colors, and wore upon

their arms, between their two elbows,

broad circlets of carved metal which

I took to be emblems of power or

authority, since the chief of them all

wore a very broad band. Their faces

were much more intelligent than their

messenger had led me to expect, and

their eyes, very large and round, and

not at all human, were the eyes of

thoughtful, reasoning creatures.

Doubled on all fours, the Chisee

crept through the circular exit,

and straightened up. As he did so,

from out of the darkness a score or

more of his fellows rushed up, gathering

around him, and blocking the exit

with their reedy legs. We could hear

than talking excitedly in high-pitched,

squeaky whispers. Then, suddenly I

received an expression from the Chisee

who wore the menore:

“Those who are with me have come

from those in power. They say one

of you, and one only, is to come with

us to our big men who will learn,

through a thing such as I wear upon

my head, that which you wish to say

to them. You are to come quickly;

at once.”

“I will come,” I replied. “Have those

with you make way—”

A heavy hand fell upon my shoulder;

a voice spoke eagerly in my ear:

“Sir, you must not go!” It was Croy,

and his voice shook with feeling. “You

are in command of the Ertak; she, and

those in her need you. Let me go! I

insist, sir!”

I turned in the darkness, quickly and

angrily.

“Mr. Croy,” I said swiftly, “do you

realize that you are speaking to your

commanding officer?”

I felt his grip tighten on my arm

as the reproof struck home.

“Yes, sir,” he said doggedly. “I do.

But I repeat that your duty commands

you to remain here.”

“The duty of a commander in this

Service leads him to the place of greatest

danger, Mr. Croy,” I informed him.

“Then stay with your ship, sir!” he

pleaded, craftily. “This may be some

trick to get you away, so that they may

attack us. Please! Can’t you see that

I am right, sir?”

I thought swiftly. The earnestness

of the youngster had touched me. Beneath

the formality and the “sirs” there

was a real affection between us.

In the darkness I reached for his

hand; I found it and shook it solemnly—a

gesture of Earth which it is hard

to explain. It means many things.

“Go, then, Andy,” I said softly. “But

do not stay long. An hour at the

longest. If you are not back in that

length of time, we’ll come after you,

and whatever else may happen, you can

be sure that you will be well avenged.

The Ertak has not lost her stinger.”

“Thank you, John,” he replied. “Remember

that I shall wear my menore.

If I adjust it to full power, and you

do likewise, and stand without the shelter

of the Ertak’s metal hull, I shall be

able to communicate with you, should

there be any danger.” He pressed my

hand again, and strode through the exit

out into the darkness, which was lit

only by a few distant stars.

The long, slim legs closed in around

him; like a pigmy guarded by the

skeletons of giants he was led quickly

away.

The minutes dragged by. There

was a nervous tension on the ship,

the like of which I have experienced

not more than a dozen times in all my

years.

No one spoke aloud. Now and again

one man would matter uneasily to another;

there would be a swift, muttered

response, and silence again. We were

waiting—waiting.

Ten minutes went by. Twenty.

Thirty.

Impatiently I paced up and down

before the exit, the guards at their

posts, ready to obey any orders instantly.

Forty-five minutes. I walked through

the exit; stepped out onto the cold,

hard earth.

I could see, behind me, the shadowy

bulk of the Ertak. Before me, a

black, shapeless blot against the star-sprinkled

sky, was the great administrative

building of the Chisee. And

in there, somewhere, was Anderson

Croy. I glanced down at the luminous

dial of my watch. Fifty minutes. In

ten minutes more—

“John Hanson!” My name reached

me, faintly but clearly, through the

medium of my menore. “This is Croy.

Do you understand me?”

“Yes,” I replied instantly. “Are you

safe?”

“I am safe. All is well. Very well.

Will you promise me now to receive

what I am about to send, without interruption?”

“Yes,” I replied, thoughtlessly and

eagerly. “What is it?”

“I have had a long conference with

the chief or head of the Chisee,”

explained Croy rapidly. “He is very

intelligent, and his people are much

further advanced than we thought.

“Through some form of communication,

he has learned of the fight with

the weird birds; it seems that they are—or

were—the most dreaded of all the

creatures of this dark world. Apparently

we got the whole brood of them,

and this chief, whose name, I gather,

is Wieschien, or something like that,

is naturally much impressed.

“I have given him a demonstration

or two with my atomic pistol and the

flashlight—these people are fairly

stricken by a ray of light directly in

the eyes—and we have reached very

favorable terms.

“I am to remain here as chief bodyguard

and adviser, of which he has

need, for all is not peaceful, I gather,

in this kingdom of darkness. In return,

he is to give up his plans to subjugate

the rest of Antri; he has sworn

to do this by what is evidently, to him,

a very sacred oath, witnessed solemnly

by the rest of his council.

“Under the circumstances, I believe

he will do what he says; in any case,

the great canal will be filled in, and

the Antrians will have plenty of time

to erect a great series of disintegrator

ray stations along the entire twilight

zone, using the broad fan rays to form

a solid wall against which the Chisee

could not advance even did they, at

some future date, carry out their plans.

The worst possible result then would

be that the people in the sunlit portion

would have to migrate from certain

sections, and perhaps would have day

and night, alternately, as do other

worlds.

“This is the agreement we have

reached; it is the only one that will

save this world. Do you approve, sir?”

“No! Return immediately, and we

will show the Chisee that they cannot

hold an officer of the Special Patrol

as a hostage. Make haste!”

“It’s no go, sir,” came the reply instantly.

“I threatened them first.

I explained what our disintegrator rays

would do, and Wieschien laughed at

me.

“This city is built upon great subterranean

passages that lead to many

hidden exits. If we show the least

sign of hostility the work will be resumed

on the canal, and, before we can

locate the spot, and stop the work, the

damage will be done.

“This is our only chance, sir, to make

this expedition a complete success.

Permit me to judge this fact from the

evidence I have before me. Whatever

sacrifice there is to make, I make gladly.

Wieschien asks that you depart at

once, and in peace, and I know this is

the only course. Good-by, sir; convey

my salutations to my other friends upon

the old Ertak, and elsewhere. And

now, lest my last act as an officer of

the Special Patrol Service be to refuse

to obey the commands of my superior

officer, I am removing the menore.

Good-by!”

I tried to reach him again, but there

was no response.

Gone! He was gone! Swallowed up

in darkness and in silence!

Dazed, shaken to the very foundation

of my being, I stood there

between the shadowy bulk of the Ertak

and the towering mass of the great silent

pile that was the seat of government

in this strange land of darkness,

and gazed up at the dark sky above

me. I am not ashamed, now, to say that

hot tears trickled down my cheeks, nor

that as I turned back to the Ertak, my

throat was so gripped by emotion that

I could not speak.

I ordered the exit closed with a wave

of my hand; in the navigating room I

said but four words: “We depart at

once.”

At the third meal of the day I

gathered my officers about me and told

them, as quickly and as gently as I

could, of the sacrifice one of their number

had made.

It was Kincaide who, when I had

finished, rose slowly and made reply.

“Sir,” he said quietly, “We had a

friend. Some day, he might have died.

Now he will live forever in the records

of the Service, in the memory of a

world, and in the hearts of those who

had the honor to serve with him. Could

he—or we—wish more?”

Amid a strange silence he sat down

again, and there was not an eye among

us that was dry.

I hope that the snappy young officer

who visited me the other day

reads this little account of bygone

times.

Perhaps it will make clear to him

how we worked, in those nearly forgotten

days, with the tools we had at

hand. They were not the perfect tools

of to-day, but what they lacked, we

somehow made up.

That fine old motto of the Service,

“Nothing Less Than Complete Success,”

we passed on unsullied to those

who came after us.

I hope these youngsters of to-day

may do as well.

IN THE NEXT ISSUE

THE TENTACLES FROM BELOW

A Complete Novelette of An American Submarine’s Dramatic Raid on Marauding “Machine-Fish” of the Ocean Floor

By Anthony Gilmore

PHALANXES OF ATLANS

Beginning a Thrilling Two-Part Novel of a Strange Hidden Civilisation

By F. V. W. Mason

THE BLACK LAMP

Another of Dr. Bird’s Amazing Exploits

By Captain S. P. Meek

THE PIRATE PLANET

The Conclusion of the Splendid Current Novel

By Charles W. Diffin

They tilted her rudders and dove to the abysm below.

The Sunken Empire

By H. Thompson Rich

Concerning the strange adventures of Professor

Stevens with the Antillians on the

floors of the mysterious Sargasso Sea.

“Then you really expect to

find the lost continent of Atlantis,

Professor?”

Martin Stevens lifted his

bearded face sternly to the reporter

who was interviewing him in his study

aboard the torpedo-submarine Nereid,

a craft of his own

invention, as she

lay moored at her

Brooklyn wharf,

on an afternoon

in October.

“My dear young man,” he said, “I

am not even going to look for it.”

The aspiring journalist—Larry Hunter

by name—was properly abashed.

“But I thought,” he insisted nevertheless,

“that you said you were going

to explore the ocean floor under the

Sargasso Sea?”

“And so I did.” Professor Stevens

admitted, a smile moving that gray

beard now and his blue eyes twinkling

merrily. “But the Sargasso, an area

almost equal to Europe, covers other

land as well—land

of far more

recent submergence

than Atlantis,

which foundered

in 9564 B. C., according to Plato.

What I am going to look for is this

newer lost continent, or island rather—namely,

the great island of Antillia,

of which the West Indies remain above

water to-day.”

“Antillia?” queried Larry Hunter,

wonderingly. “I never heard of it.”

Again the professor regarded his interviewer

sternly.

“There are many things you have

never heard of, young man,” he told

him. “Antillia may be termed the missing

link between Atlantis and America.

It was there that Atlantean culture

survived after the appalling catastrophe

that wiped out the Atlantean

homeland, with its seventy million inhabitants,

and it was in the colonies

the Antillians established in Mexico

and Peru, that their own culture in

turn survived, after Antillia too had

sunk.”

“My Lord! You don’t mean to say

the Mayas and Incas originated on that

island of Antillia?”

“No, I mean to say they originated

on the continent of Atlantis, and that

Antillia was the stepping stone to the

New World, where they built the

strange pyramids we find smothered in

the jungle—even as thousands of years

before the Atlanteans established colonies

in Egypt and founded the earliest

dynasties of pyramid-building

Pharaohs.”

Larry was pushing his pencil

furiously.

“Whew!” he gasped. “Some story,

Professor!”

“To the general public, perhaps,” was

the reply. “But to scholars of antiquity,

these postulates are pretty well

known and pretty well accepted. It

remains but to get concrete evidence,

in order to prove them to the world at

large—and that is the object of my

expedition.”

More hurried scribbling, then:

“But, say—why don’t you go direct

to Atlantis and get the real dope?”

“Because that continent foundered

so long ago that it is doubtful if any

evidence would have withstood the

ravages of time,” Professor Stevens

explained, “whereas Antillia went

down no earlier than 200 B. C., archaeologists

agree.”

“That answers my question,” declared

Larry, his admiration for this

doughty graybeard rising momentarily.

“And now, Professor, I wonder if

you’d be willing to say a few words

about this craft of yours?”

“Cheerfully, if you think it would

interest anyone. What would you care

to have me say?”

“Well, in the first place, what does

the name Nereid mean?”

“Sea-nymph. The derivation is from

the Latin and Greek, meaning daughter

of the sea-god Nereus. Appropriate,

don’t you think?”

“Swell. And why do you call it a

torpedo-submarine? How does it differ

from the common or navy variety?”

Professor Stevens smiled.

It was like asking what was the

difference between the sun and the

moon, when about the only point of resemblance

they had was that they were

both round. Nevertheless, he enumerated

some of the major modifications

he had developed.

Among them, perhaps the most radical,

was its motive power, which was

produced by what he called a vacuo-turbine—a

device that sucked in the

water at the snout of the craft and expelled

it at the tail, at the time

purifying a certain amount for drinking

purposes and extracting sufficient

oxygen to maintain a healthful atmosphere

while running submerged.

Then, the structure of the Nereid was

unique, he explained, permitting it to

attain depths where the pressure

would crush an ordinary submarine,

while mechanical eyes on the television

principle afforded a view in all

directions, and locks enabling them to

leave the craft at will and explore the

sea-bottom were provided.

This latter feat they would accomplish

in special suits, designed on the

same pneumatic principle as the torpedo

itself and capable of sustaining

sufficient inflation to resist whatever

pressures might be encountered, as well

as being equipped with vibratory sending

and receiving apparatus, for maintaining

communication with those left

aboard.

All these things and more Professor

Stevens outlined, as Larry’s

pencil flew, admitting that he had

spent the past ten years and the best

part of his private fortune in developing

his plans.

“But you’ll get it all back, won’t

you? Aren’t there all sorts of Spanish

galleons and pirate barques laden with

gold supposed to be down there?”

“Undoubtedly,” was the calm reply.

“But I am not on a treasure hunt,

young man. If I find one single sign

of former life, I shall be amply rewarded.”

Whereupon the young reporter regarded

the subject of his interview

with fresh admiration, not unmingled

with wonder. In his own hectic world,

people had no such scorn of gold. Gee,

he’d sure like to go along! The professor

could have his old statues or

whatever he was looking for. As for

himself, he’d fill up his pockets with

Spanish doubloons and pieces of eight!

Larry was snapped out of his trance

by a light knock on the door, which

opened to admit a radiant girl in

creamy knickers and green cardigan.

“May I come in, daddy?” she inquired,

hesitating, as she saw he was

not alone.

“You seem to be in already, my dear,”

the professor told her, rising from his

desk and stepping forward.

Then, turning to Larry, who had also

risen, he said:

“Mr. Hunter, this is my daughter,

Diane, who is also my secretary.”

“I am pleased to meet you, Miss

Stevens,” said Larry, taking her hand.

And he meant it—for almost anyone

would have been pleased to meet Diane,

with her tawny gold hair, warm olive

cheeks and eyes bluer even than her

father’s and just as twinkling, just as

intelligent.

“She will accompany the expedition

and take stenographic notes of everything

we observe,” added her father, to

Larry’s amazement.

“What?” he declared. “You mean to

say that—that—”

“Of course he means to say that I’m

going, if that’s what you mean to say,

Mr. Hunter,” Diane assured him. “Can

you think of any good reason why I

shouldn’t go, when girls are flying

around the world and everything else?”

Even had Larry been able to think

of any good reason, he wouldn’t have

mentioned it. But as a matter of fact,

he had shifted quite abruptly to an entirely

different line of thought. Diane,

he was thinking—Diana, goddess of the

chase, the huntress! And himself,

Larry Hunter—the hunter and the

huntress!

Gee, but he’d like to go! What an

adventure, hunting around together on

the bottom of the ocean!

What a wild dream, rather, he

concluded when his senses returned.

For after all, he was only a

reporter, fated to write about other

people’s adventures, not to participate

in them. So he put away his pad and

pencil and prepared to leave.

But at the door he paused.

“Oh, yes—one more question. When

are you planning to leave, Professor?”

At that, Martin Stevens and his

daughter exchanged a swift glance.

Then, with a smile, Diane said:

“I see no reason why we shouldn’t

tell him, daddy.”

“But we didn’t tell the reporters

from the other papers, my dear,” protested

her father.

“Then suppose we give Mr. Hunter

the exclusive story,” she said, transferring

her smile to Larry now. “It

will be what you call a—a scoop. Isn’t

that it?”

“That’s it.”

She caught her father’s acquiescing

nod. “Then here’s your scoop, Mr.

Hunter. We leave to-night.”

To-night! This was indeed a scoop!

If he hurried, he could catch the late

afternoon editions with it.

“I—I certainly thank you, Miss

Stevens!” he exclaimed. “That’ll make

the front page!”

As he grasped the door-knob, he

added, turning to her father:

“And I want to thank you too, Professor—and

wish you good luck!”

Then, with a hasty handshake, and a

last smile of gratitude for Diane, he

flung open the door and departed, unconscious

that two young blue eyes

followed his broad shoulders wistfully

till they disappeared from view.

But Larry was unaware that he had

made a favorable impression on

Diane. He felt it was the reverse. As

he headed toward the subway, that

vivid blond goddess of the chase was

uppermost in his thoughts.

Soon she’d be off in the Nereid, bound

for the mysterious regions under the

Sargasso Sea, while in a few moments

he’d be in the subway, bound under the

prosaic East River for New York.

No—damned if he would!

Suddenly, with a wild inspiration,

the young reporter altered his course,

dove into the nearest phone booth and

got his city editor on the wire.

Scoop? This was just the first installment.

He’d get a scoop that would

fill a book!

And his city editor tacitly O. K.’d

the idea.

With the result that when the Nereid

drew away from her wharf that night,

on the start of her unparalleled voyage,

Larry Hunter was a stowaway.

The place where he had succeeded

in secreting himself was a small

storeroom far aft, on one of the lower

decks. There he huddled in the darkness,

while the slow hours wore away,

hearing only the low hum of the craft’s

vacuo-turbine and the flux of water

running through her.

From the way she rolled and pitched,

he judged she was still proceeding

along on the surface.

Having eaten before he came aboard,

he felt no hunger, but the close air and

the dark quarters brought drowsiness.

He slept.

When he awoke it was still dark, of

course, but a glance at his luminous

wrist-watch told him it was morning

now. And the fact that the rolling and

pitching had ceased made him believe

they were now running submerged.

The urge for breakfast asserting itself,

Larry drew a bar of chocolate

from his pocket and munched on it.

But this was scanty fare for a healthy

young six-footer, accustomed to a liberal

portion of ham and eggs. Furthermore,

the lack of coffee made him realize

that he was getting decidedly

thirsty. The air, moreover, was getting

pretty bad.

“All in all, this hole wasn’t exactly

intended for a bedroom!” he reflected

with a wry smile.

Taking a chance, he opened the door

a crack and sat there impatiently, while

the interminable minutes ticked off.

The Nereid’s turbine was humming

now with a high, vibrant note that indicated

they must be knocking off the

knots at a lively clip. He wondered

how far out they were, and how far

down.

Lord, there’d be a riot when he

showed up! He wanted to wait till

they were far enough on their way so

it would be too much trouble to turn

around and put him ashore.

But by noon his powers of endurance

were exhausted. Flinging open

the door, he stepped out into the corridor,

followed it to a companionway and

mounted the ladder to the deck above.

There he was assailed by a familiar

and welcome odor—food!

Trailing it to its origin, he came to

a pair of swinging doors at the end of

a cork-paved passage. Beyond, he saw

on peering through, was the mess-room,

and there at the table, among a

number of uniformed officers, sat Professor

Stevens and Diane.

A last moment Larry stood there,

looking in on them. Then, drawing a

deep breath, he pushed wide the swinging

doors and entered with a cheery:

“Good morning, folks! Hope I’m not

too late for lunch!”

Varying degrees of surprise

greeted this dramatic appearance.

The officers stared, Diane gasped, her

father leaped to has feet with a cry.

“That reporter! Why—why, what

are you doing here, young man?”

“Just representing the press.”

Larry tried to make it sound nonchalant

but he was finding it difficult

to bear up under this barrage of disapproving

eyes—particularly two very

young, very blue ones.

“So that is the way you reward us

for giving you an exclusive story, is

it?” Professor Stevens’ voice was

scathing. “A representative of the

press! A stowaway, rather—and as

such you will be treated!”

He turned to one of his officers.

“Report to Captain Petersen that we

have a stowaway aboard and order him

to put about at once.”

He turned to another.

“See that Mr. Hunter is taken below

and locked up. When we reach New

York, he will be handed over to the

police.”

“But daddy!” protested Diane, as

they rose to comply, her eyes softening

now. “We shouldn’t be too severe with

Mr. Hunter. After all, he is probably

doing only what his paper ordered him

to.”

Gratefully Larry turned toward

his defender. But he couldn’t

let that pass.

“No, I’m acting only on my own

initiative,” he said. “No one told me to

come.”

For he couldn’t get his city editor

involved, and after all it was his own

idea.

“You see!” declared Professor

Stevens. “He admits it is his own doing.

It is clear he has exceeded his

authority, therefore, and deserves no

sympathy.”

“But can’t you let me stay, now that

I’m here?” urged Larry. “I know

something about boats. I’ll serve as a

member of the crew—anything.”

“Impossible. We have a full complement.

You would be more of a

hindrance than a help. Besides, I do

not care to have the possible results of

this expedition blared before the public.”

“I’ll write nothing you do not approve.”

“I have no time to edit your writings,

young man. My own, will occupy me

sufficiently. So it is useless. You are

only wasting your breath—and mine.”

He motioned for his officers to carry

out his orders.

But before they could move to do so,

in strode a lean, middle-aged Norwegian

Larry sensed must be Captain

Petersen himself, and on his weathered

face was an expression of such gravity

that it was obvious to everyone something

serious had happened.

Ignoring Larry, after one brief

look of inquiry that was answered

by Professor Stevens, he reported

swiftly what he had to say.

While cruising full speed at forty

fathoms, with kite-aerial out, their

wireless operator had received a radio

warning to turn back. Answering on

its call-length, he had demanded to

know the sender and the reason for the

message, but the information had been

declined, the warning merely being repeated.

“Was it a land station or a ship at

sea?” asked the professor.

“Evidently the latter,” was the reply.

“By our radio range-finder, we determined

the position at approximately

latitude 27, longitude 65.”

“But that, Captain, is in the very

area we are headed for.”

“And that, Professor, makes it all the

more singular.”

“But—well, well! This is indeed peculiar!

And I had been on the point

of turning back with our impetuous

young stowaway. What would you

suggest, sir?”

Captain Petersen meditated, while

Larry held his breath.

“To turn back,” he said at length, in

his clear, precise English, “would in

my opinion be to give the laugh to

someone whose sense of humor is already

too well developed.”

“Exactly!” agreed Professor Stevens,

as Larry relaxed in relief. “Whoever

this practical joker is, we will show

him he is wasting his talents—even

though it means carrying a supernumerary

for the rest of the voyage.”

“Well spoken!” said the captain.

“But as far as that is concerned, I think

I can keep Mr. Hunter occupied.”

“Then take him, and welcome!”

Whereupon, still elated but now

somewhat uneasy, Larry accompanied

Captain Petersen from the mess-room;