Frontispiece.

Title: Through green glasses

Andy Merrigan's great discovery, and other Irish tales

Author: Edmund Downey

Illustrator: M. Fitzgerald

Release date: October 28, 2025 [eBook #77138]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1887

Credits: Andrew Scott, Emmanuel Ackerman, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

ANDY MERRIGAN’S

GREAT DISCOVERY

AND OTHER IRISH TALES

BY

F. M. ALLEN

ILLUSTRATED BY M. FITZGERALD

NEW YORK

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1887

Copyright, 1887,

By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Introduction | 1 |

| Andy Merrigan’s Great Discovery | 5 |

| From Portlaw to Paradise | 44 |

| King John and the Mayor | 63 |

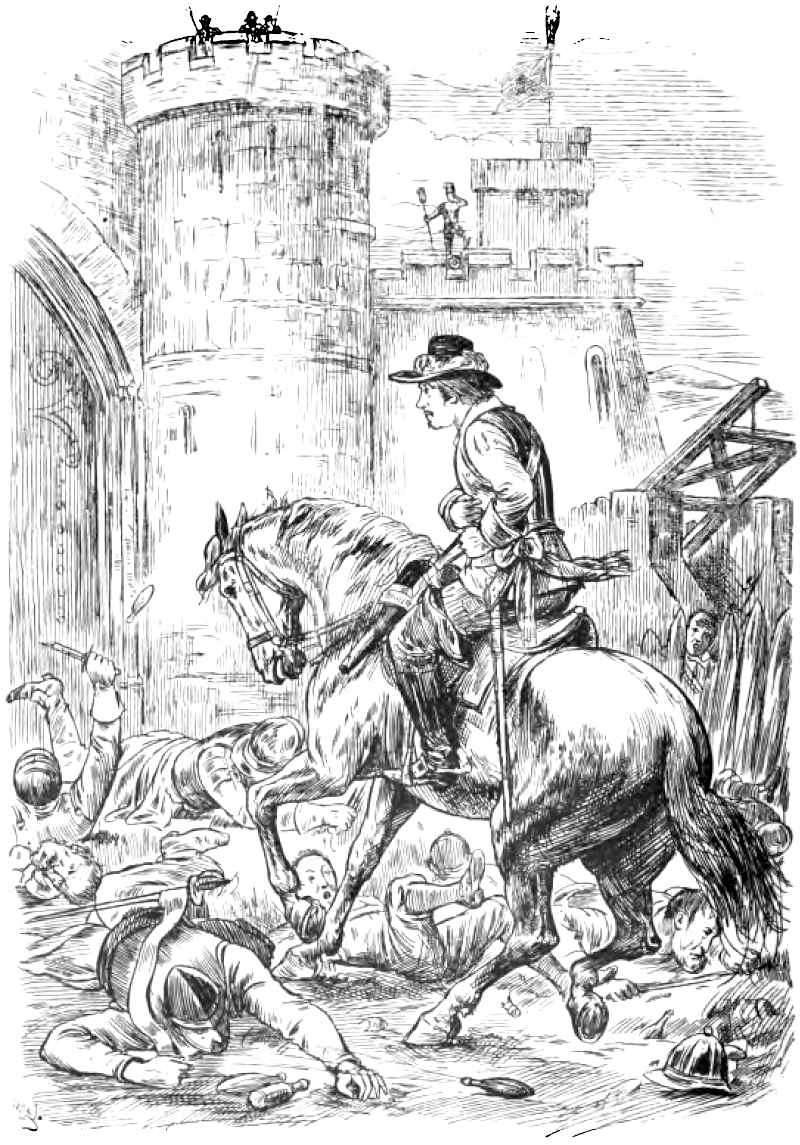

| The Wonderful Escape of James the Second | 83 |

| The Last of the Dragons | 123 |

| The Siege of Don Isle | 143 |

| Raleigh in Munster | 198 |

| It was once my fortune to meet in a southern Irish town a little old man whose mind was a storehouse of strange legendary lore Frontispiece | ||

| Andy Merrigan’s Great Discovery | To face p. | 5 |

| From Portlaw to Paradise | ” | 44 |

| King John and the Mayor | ” | 63 |

| The Escape of James the Second | ” | 83 |

| The Last of the Dragons | ” | 123 |

| The Siege of Don Isle | ” | 143 |

| Raleigh in Munster | ” | 198 |

[Pg 1]

It was once my fortune to meet in a southern Irish town a little old man whose mind was a storehouse of strange legendary lore. He was thoroughly illiterate, but he had contrived to pick up in some way a peculiar collection of quasi-historical facts and fables. These he winnowed through his brain, rejecting the greater part of the corn and retaining all the chaff; and this mixture he would, like Æsop of old, retail solemnly to any chance customer.

Dan—for such was his christian name—possessed an imagination of a peculiarly circumscribed character. His vision extended little further than his own tip-tilted nose, and around everything he[Pg 2] wrapped a local, nay a personal, mantle. The kings, the princes, the chieftains of eld he clothed in his own shabby garments—even the saints (whom he reverenced) fared little better at his hands. All the characters introduced in his legendary yarns thought as Dan thought, acted as he would, in all probability, have acted, and spoke with his own delightful brogue.

I may here observe, parenthetically, that the illiterate Irish story-teller possesses—so far as my experience goes—a vocabulary which is singularly simple and lucid. Most of the words he employs are either monosyllabic or dissyllabic. If the brogue were eliminated it would be found that he adopts a style which, so far as the choice of language is concerned, might be studied with advantage by those who (like myself) strive vainly after simplicity of diction. Of course no uneducated Irishman ever attempts to tread the mazes of “shall and will,” nor is he addicted to nominatives which agree with their verbs. He is, moreover, somewhat given to the mixing of tenses; and[Pg 3] in the course of a lengthy narrative, he usually flies to the refuge of many of our modern novelists—the present tense.

Dan’s style of narration had all the faults and the merits which I have endeavoured to point out, but Dan possessed one quality which atoned for most of his mixed tenses and for all his ill-mated nominatives and verbs—an extraordinary fund of humour. Of this possession he seemed, however, to live in blissful ignorance. He seldom smiled, and, in the general acceptation of the word, he never laughed. His laughing muscles were, possibly, situated in his shoulders, for when he told a good story, or when he heard one from a neighbour, his shoulders would shake and quiver with a motion prolonged and jelly-like.

Chronology had no meaning and no terrors for Dan. To him the early Milesians, St. Patrick, Brian the Brave, Cromwell, and even “the great Bonypart” were, practically speaking, contemporaneous. In recounting any of the doughty deeds of the First Emperor he always kept before your mind’s[Pg 4] eye a picture of that “ould anshent warrior” (possibly he confounded him with Hannibal) crossing the summits of the Alps on a milk-white charger. To Dan, Waterloo and St. Helena were purely mythical—at all events his “Bonypart” had never met with disaster nor ever endured exile. The only celebrity whom he condescended to view in a commonplace light was Garibaldi. He firmly believed the Italian patriot was a renegade Tipperaryman named Garret Baldwin, and often I have heard Dan express his unbounded contempt for the miserable Munsterman who had “gone and taken up arms agen his Holiness the Pope.”

I have listened to many and many a romance as it fell from Dan’s lips, and it occurred to me that if I could speak with his voice, I might, in attempting to reproduce some of his yarns, be able to afford amusement to a larger audience than it was Dan’s province to cater for.

[Pg 5]

Many an’ many a hundhred year ago there lived at Roche’s Point, just at the enthrance of Cork harbour, a fine sthrappin’ young fellow named Andy Merrigan. He owned as nate a thrawler as you could see from this to the Land’s End, an’ ’twas the grand fisherman he was intirely.

Andy was tall and sthrong, wud long black hair fallin’ over his showldhers, an’ eyes that burned undher his brows like fires of coal. He was very dark in himself for a young man, an’ all the neighbours wor more or less in dhread of him.

Andy never sailed his thrawler in company wud any of the other fishermen in Cork Harbour; an’ ’twas always of a dirty night an’ whin the win’ was blowin’ hard an’ the say was high that he used to[Pg 6] cast off from his moorin’s; an’ thin the neighbours wouldn’t see him or hear of him again maybe for weeks an’ weeks. But whenever he did come back it was always wud a boat-load of fish; an’ thin he would stop ashore for a spell an’ spend whips of money in all kinds of divarsion.

Of coorse there wor plenty of back-bithers in Cork Harbour that had the hard word agen Andy; but divil a wan of ’em had the courage ever to say anything crooked forenenst him, for he had a fist as firm an’ as heavy as a half hundredweight, an’ he wasn’t shy of usin’ it on an emergency. There wor some whispers that Andy was a pirate king in saycrit, an’ others said ’twas a wrecker he was an’ that his fires wor often seen on the coast of Clare.

No wan used to sail in the thrawler wud Andy exceptin’ two cousins of his by the mother’s side, named Pat Carroll and Mick Egan, an’ the cousins wor just as dark an’ as dangerous as Andy himself.

Well, wan day, afther the longest voyage he had[Pg 7] ever made, Andy dhropped his anchor at the quay of Cork; an’ laivin’ Pat and Mick an’ a new hand, a cabin boy, in charge of the thrawler, he started to walk to the Rock of Cashel.

Three days an’ three nights he was on the road—for of course this was in the oulden times before a horse-an’-car, let alone a railway thrain was invinted—an’ on the mornin’ of the fourth day he found himself undher the Rock.

“Good morra, major,” says he to the sinthry that was walkin’ up an’ down outside the enthrance.

“Good morra, sthranger,” says the sinthry. “Have you been long on the thramp?”

“Three days an’ three nights,” says Andy.

“An’ where are you from?” axes the sinthry.

“The Cove of Cork,” says Andy, who generally had a short way of spaykin’ in conversation.

“An’ what’s your business here?” axes the sinthry.

“To see the King of Munsther,” says Andy.

Begor the sinthry began to laugh thin, an’ says[Pg 8] he, “P’raps ’tis a poor relation of the King’s you are?”

“No, nor a rich wan aither,” says Andy; “but I came to see him all the same.”

“Have you an ordher?” says the sinthry.

“No,” says Andy.

“Thin I wondhers at your cheek,” says the sinthry.

“You’re welcome,” says Andy.

“Arrah get on out of this about your business,” says the sinthry, “or I’ll give you a taste of the fore-fut of my pike just to remind you of who you’re spaykin’ to.”

“Keep your ould iron to yerself,” says Andy. “I’m not a marine-store dayler.”

“Faix an’ that’s what I thought you wor,” says the sinthry, thryin’ to have the laugh agen Andy.

“Did you?” says Andy, lookin’ very black. “Look at here,” says he, liftin’ his shut fist an’ givin’ the Rock of Cashel a box of it that knocked splinthers of stone flyin’ across the road, “did[Pg 9] you ever meet a marine-store dayler that could do that?”

Begor, the sinthry turned as white as a ghost, an’ says he, “Who are you at all, my fine man?”

“Andy Merrigan from Roche’s Point is my name an’ addhress,” says Andy; “an’ if you don’t take that up to the king this minute I’ll undhermine the foundations before I breaks my fast.”

The sinthry saw there ’ud be no use in rousin’ the timper of a man wud a fist like Andy’s, so he blew his thrumpet an’ another soger answered the call.

“Tell King Cormac”—for that was the King of Munsther’s name—says the sinthry, “there’s a sthranger here called Andy Merrigan from Roche’s Point, that wants a word wud him; and tell him from me,” says he, “that he’d best see him at wance.”

Andy wasn’t kept waitin’ long, for in about five minutes the messenger came back to say King Cormac would see him if he would come upstairs.[Pg 10] So Andy mounted the Rock and was shown into the King’s dhrawin’-room.

“Laive on yer hat,” says King Cormac, who was sittin’ in an arm-chair at a big fire, “for there’s a powerful dhraught up here, an’ maybe ’tis ketch cowld you would.”

“Thank ye kindly,” says Andy; “but sure I’m used to hurricanes, an’ I’d feel more at my aise if I wor to keep my hat in my hand.”

“Well, plaize yerself,” says King Cormac, givin’ the fire a stir wud a goolden poker. “What’s your business?” says he.

“I’m a man of few words,” says Andy, “an’ I’ll not enther into a long rigmarole.”

“I’m glad of that,” says King Cormac, “for I can’t give you more than ten minutes by the clock.”

“Faith thin if you knew what a wondherful plan I have to lay before you I think you’d be glad to spare me the whole run of a day,” says Andy, wud a toss of his head.

“That’s what ye all says,” laughs the King.

[Pg 11]

“Maybe,” says Andy; “but, as I’ve towld you before, I’m a man of few words.”

“I suppose you saves your breath to cool your porridge,” says the King, who had an aggravatin’ way of givin’ a sthranger ten minutes’ talk wud him an’ of squandherin’ all the time in banther.

“Well,” says Andy, “to go straight to the point—”

“Roche’s Point, is it?” intherrupts the King.

“No, nor potatoes an’ point aither,” says Andy, who saw through the thricks of the King. “An’ let me tell yer majesty,” says he, “that if you don’t give fair heed to me I’ll take meself an’ me plan straight over to Tara’s Halls.”

“Keep your hair on,” says King Cormac, seein’ that Andy was sore vexed.

“’Tisn’t aisy to do that wud the draught,” says Andy, lookin’ as black as tundher; “but I’ll do my endeavours; an’ you may thank yourself, if you lose the chance of a kingdom that I’m afther discoverin’ a hundhred times as big as Munsther.”

“What’s that you say, my man?” says King[Pg 12] Cormac, turnin’ round quickly in his aisy chair an’ lookin’ hard at Andy.

“Well, will you hear me fair?” says Andy, “clock or no clock?”

“I will,” says the King, for his cur’osity was on the sthretch at the sthrange remark that came from Andy.

“I’ll take you at your word, thin,” says Andy; “an’ this is my story an’ my plan. You must know,” says he, “that I’m the greatest sailor in these parts, an’ that win’ or weather, say or storm, have no terrors for me. Often I goes hundhreds an’ hundhreds of miles out into the western ocean if the fish is scarce in shore, an’ for that raison the cowardly bla’guards that are afeard to venture out of sighth of land tells stories of me behind my back. I mintion this,” says Andy, “fearin’ that if yer majesty came to Cork you’d hear things said about me that might turn you agen me, an’ I want to put you on yer guard beforehand.”

“But what about this tundherin’ big counthry[Pg 13] you wor spaykin’ of?” axes King Cormac, who didn’t care a thrauneen about Andy an’ his back-bithers, but was aiger to hear about the new kingdom.

“I’m comin’ to it,” says Andy.

“I thought you wor there already,” says the King, chucklin’ undher his breath.

“Look at here,” says Andy, “maybe you’d like me to make a present of it to the King of all Ireland over at Tara beyant? If that’s your mind best say so at wance.”

“Arrah, don’t be so quick in your temper,” says King Cormac. “Sure a man must have his joke now an’ again. Go on, Andy,” says he, “tell us all about it, avic.—Maybe ’tis dhry you are. I have a nice dhrop of the hard stuff here, if that’s in your line at all.”

“Begor,” says Andy, “I was never known to turn my back on a good thing.”

So the King opens a big cupboard an’ tuk out a black bottle. “Say whin,” says he to Andy, pourin’ out the whisky into a tumbler for him.

[Pg 14]

“That’ll do,” says Andy, whin the tumbler was more than three parts full.

“You didn’t laive much room for the wather,” says the King.

“Wather, is it?” says Andy. “Arrah, my dear man, ’tis deluged enough wud wather I usually do be. Anyhow I prefers it nate,” says he, tossin’ off the tumbler-full at wan go.

“’Tis a sthrong man you are!” says King Cormac. “There isn’t a tear in your eye nor a hair turned on you, an’ that’s new Cork whisky, twinty over proof.”

“I’m used to it,” says Andy; “an’ use is second nature, I’m towld.”

“Well, go on wud yer story now,” says the King, “for I’m dyin’ to hear about this new counthry you’ve discovered. Did you find a mare’s nest in it?” says he, pourin’ a dhrop out of the bottle into a tumbler for himself.

“No, nor a cuckoo’s aither,” says Andy. “’Pon my song, I dunno whether ’tis humbuggin’ me you are or what.”

[Pg 15]

“Well, I’ll be as sayrious as Solomon for the rest of the intherview,” says King Cormac. “I see you’re not used to the ways of the quality.”

“You’re right there,” says Andy. “I’m a plain man at the best, a plain dayler an’ a plain spayker; an’ this is my story. Last voyage I sailed out of Cork wud my two cousins, Mike Egan and Pat Carroll, an’ havin’ business round on the coast of Clare I put into the Shannon for a spell, an’ there I shipped a new hand, a young Scotch lad named Sandy, as a cabin boy.”

“What’s his other name?” axes King Cormac, takin’ out his note book, “for I likes always to have full particulars.”

“Hook is his surname,” says Andy.

“Thin,” says King Cormac, “when you left the Shannon, I suppose I may say you tuk your Hook?”

“Just as you plaize,” says Andy, not heedin’ the joke; “an’ as fish wor scarce in by the coast I put the thrawler on a long reach wud her head to the westhard. Well, afther a week’s sail an’ no fish,[Pg 16] a terrible gale came out from the nor’a’d and aisthard, an’ I was obliged to run the thrawler before the win’ undher bare poles. Four weeks afther startin’ from the Shannon the cabin boy shouts out ‘Land-o;’ an’ sure enough we sighthed a point of land which we christened Sandy Hook, afther the boy.”

“Well?” says the King, his cur’osity fairly roused.

“The same day,” says Andy, “we found ourselves in an iligant bay wud a most beautiful counthry surroundin’ it. Of coorse we wor clane out of provisions for some days, an’ the sighth of the new land where no wan ever thought there was a dhry spot before nearly dhrove us out of our wits wud joy. We ran the thrawler right in for the shore an’ beached her safely, an’ thin we jumped ashore in ordher to see where we cud get a bite an’ a sup. In about half a pig’s whisper the beach was crowded wud niggers, wud scarcely a screed of clothes on ’em. There was a big man wud a necklace hangin’ from his showldhers at the head of[Pg 17] the crowd that looked like a chief nigger, so I goes up to him an’ says I, ‘We’re frindly, I gives you my word; an’, what’s more, we’re famishin’ wud hunger an’ thirst. If you haven’t a rasher of bacon handy could you give us a fill of tobaccy?’ The chief shuk his head as much as to say ‘I can’t undherstand you,’ and he begins to jabber away in some sort of lingo I couldn’t make head or tail of. ‘What’ll we do at all, at all?’ says I to meself; an’ thin a grand idaya sthruck me all of a suddint.

“I learnt the deaf-an’-dumb alphabet at school for divarsion, and I cud talk on my fingers wud the greatest dummy in Cork, so I began to make signs to the chief, wud my hands, an’ begor the ould nigger twigged what I was doin’ at wance. So he beckoned to a man in the crowd, an’ a little fellow, whom I aftherwards found was the headmasther of a deaf-an’-dumb school, stepped out forenest me an’ in a minute we were hard at it, talkin’ to aich other on our fingers. ‘Who or what are ye at all, at all?’ axes the little nigger.[Pg 18] ‘We’re christhins, to begin wud,’ says I, answerin’ him back of coorse on my fingers. ‘What’s christhins?’ says he. ‘Did you never hear of St. Pathrick?’ says I. ‘Never,’ says he. Indeed I might have made sure that ’ud be the answer I’d get, for at laiste St. Pathrick if he ever visited the niggers would have inthroduced a tailor among ’em. ‘Well,’ says I, puzzled to know how to explain matthers, ‘we’re all Irishmen too, exceptin’ the boy here, an’ he comes from Scotland.’ ‘What’s Irishmen?’ says he. ‘Arrah,’ says I, ‘is it jokin’ you are, or do you mane to tell me you never heard of ould Ireland?’ ‘Never,’ says the nigger; ‘’tis a puzzle to me to make sense out of you at all. Maybe,’ says he, wud a grin on him like a monkey, ‘you’re something else?’ ‘We are, thin,’ says I, ‘whether you laughs or no. We’re Corkmen—three parts of us, at any rate.’ ‘Three parts of ye is cork!’ says he; ‘an’ what’s the other part made of?’ ‘Arrah, my dear man,’ says I, ‘there’s no use in losin’ my time an’ my temper thryin’ to enlighten your ignorance. I’ll wait till I larns to spake your langwidge, an’[Pg 19] thin I’ll be able to make you undherstand me properly. An’ now,’ says I, ‘will you answer me what I’ll ax you?’ ‘Wud pleasure,’ says the little nigger. ‘What counthry is this?’ says I. ‘Injy,’ says he. ‘An’ are ye all Red Injuns?’ says I. ‘We are,’ says he, ‘every mother’s son of us.’ ‘What’s the name of this town an’ harbour?’ says I, pointin’ to the hape of mud cabins in shore, an’ to the beautiful bay forenest us. ‘New York,’ says he. ‘An’ who is the big man at the head of ye there?’ says I, pointin’ to the nigger, who had gone up the beach a bit wud some of the faymales. ‘I mane the chap I made the first offer at discoorsin’ to.’ ‘He’s the King of New York,’ says he. ‘A wondher he don’t dhress himself more dacently!’ says I. ‘Dhress!’ says he. ‘Why ’tis in full dhress he is now.’ ‘An’ is a necklace an’ a rub of paint full dhress in these parts?’ says I. ‘It is,’ says the little nigger. ‘It doesn’t cost over much to be fashionable here,’ says I. ‘No’, says he, ‘we spend the bulk of our money on aitin’ and dhrinkin’.’

“Begor, yer majesty! the mintion of grub gave[Pg 20] me a pain in the stomach, so I axed the little man if he could knock up a male for us, as we were all ready to dhrop wud the hunger. ‘I’ll spake to the King,’ says he. So he goes over to the big nigger, an’ I suppose he towld him all he could about us, an’ whatever it was he towld him it made the king laugh a dale. Then the little nigger beckoned to me to come over to the King. To tell the thruth I felt a thrifle ashamed of goin’ over near the women, but, faix! the hunger takes most of the timidness out of a man, so I plucked up the courage, an’ over I goes to the King. Well, by manes of the intarpinther—the little nigger—the King and meself had a long discoorse, but the dickens a bit of me could make the poor ignorant darkey undherstand that we wor human craychurs like himself; and maybe you’ll think ’tis a lie I’m tellin’ you, King Cormac,” says Andy, “but ’tis as thrue as Gospel that the King of New York thought, from what the little nigger was afther tellin’ him, that three-quarthers of us was made of cork, an’ that what he could see of us—I mane our[Pg 21] face an’ our hands—was the only naatural part of us.”

“It bates all,” says King Cormac, laughin’ hearty. “Divil the like ever I heard! But go on wud your story, Misther Merryan.”

“Well,” says Andy, “I saw there was no use just thin in thryin’ to persuade the King of New York that it wasn’t samples of virgin cork three parts of us wor; but, faith! I had an onaisy feelin’ that he might have it in his mind to cut us up for cork fendhers an’ the like, and you may be sure I had no intintion of allowin’ meself to be made into a sthopper for a bung-hole, so I towld him if he’d give me a private intherview in the coorse of a few days, when I’d have picked up some of the lingo, I could explain matthers to him. ‘In the manetime,’ says I to him, ‘for the love of goodness, give the four of us something to fill our insides wud!’ ‘What ’ud you like?’ says the King of New York. ‘Well, if it’s no inconvaynience to the coort,’ says I, ‘we’d prefer a good male of bacon and cabbage to anything you could[Pg 22] offer; and if you could see your way to let us moisten that same wud some whisky-an’-wather, I’d be undher a heavy load of obligation to you.’ Well, wud that the King gev ordhers to have the biggest side of bacon in the palace taken off the hooks an’ boiled for us; ‘an’ while ’tis cookin’,’ says he, ‘maybe you’d like to break your fast on the remains of a cowld showldher of mutton left from Sunday’s dinner?’”

“That reminds me,” says King Cormac, “that I never axed you if you had a mouth on you. I think there’s the remains of a half pig’s head here,” says he, goin’ over to the cupboard and taking a heavy goold dish out of it.

“Faix!” says Andy, “if you wor thryin’ to discover what was in my mind this minute, you couldn’t have hit the mark more close. I’m nearly famished wud the hunger, but, of coorse, I didn’t like to be makin’ meself too much at home on a first visit, or I’d have mintioned the fact before.”

“Betther late than never,” says King Cormac.[Pg 23] “Hunger is the best sauce, an’ the chapest too, so you’ll excuse me for not offerin’ you anything barrin’ the knife an’ fork.”

“Don’t mintion it,” says Andy.

“’Tis a nice piece of mate,” says King Cormac. “You find it tindher, don’t you?”

“Like a spring chicken,” says Andy.

“I suppose you can talk while you’re aitin’?” says King Cormac.

“I can,” says Andy, though the words nearly choked him. Of coorse, he had to thry an’ put on his quality manners when he was discoorsin’ wud a king, but it tuk him all his time to spake plain wud his mouth full.

“Go on, thin,” says King Cormac. “What I’m anxious to hear,” says he, “is what’s the size of this new counthry, an’ what soort of a place it is in general.”

“That’s what I’m comin’ to,” says Andy.

“Thin come to it quick,” says King Cormac, “for half my mornin’ is gone already, an’ I’ve a dale of business to attend to.”

[Pg 24]

Andy’s hunger was partly satisfied by this, so he laid down his knife an’ fork, an’ says he, “Well, to hurry matthers up, this Injy is a mighty big counthry. They tell me ’twould take a man, walkin’ twinty mile a day, nearly half a year to get to the other side of it.”

“Dhraw it mild,” says King Cormac.

“Faith! ’tis the thruth I’m telling you,” says Andy. “An’, now,” says he, “I comes to the point where I’ll have to ax your majesty to give me full considheration. I spent the best part of two months wud the Injuns, an’ ’tis right well they thrated me. The innocent craychurs have no idaya at all of the value of land; all they thinks of is aitin’ an’ dhrinkin’, crackin’ jokes, an’ playing tambourines. Just to show what sort they are, I may tell you that wan day, afther I had made christhins of ’em all an’ taught ’em how to spake English, the King axed me to write me name in the visithors’ book, so I wrote down wud a flourish, ‘A. Merrigan.’ He looks at the writin’, an’ says he, ‘For the future we’ll call ourselves afther you.’ So the word wint[Pg 25] forth that all the Injuns all over the counthry wor to be known in future as Amerrigans, an’ they calls the counthry for short, Amerriga. They has a way of choppin’ their words, you see.”

“’Tis a proud man you ought to be,” says King Cormac. “Do you mind shakin’ hands wud me?”

So, begor, Andy an’ the King of Munsther shuk hands, an’ the tears rowled down King Cormac’s cheeks wud the hard grip Andy fastened on him, but he was a proud man, an’ wouldn’t let on he was hurt if a mule wor to give him a kick in the ribs.

“Well,” says Andy, “even callin’ the counthry afther me wouldn’t satisfy ould Sambo—the King of New York, I mane—but the next thing he did was to summon a meetin’ of his head follyers; an’, wudout a word of a lie, they towld me they had made up their minds to give me a present of the whole counthry if I’d marry the King of New York’s eldest daughther.”

“An’ did you take the offer?” says King Cormac.

[Pg 26]

“Of coorse I did,” says Andy; “an’ not to be outdone by a parcel of niggers in ginerosity, the first thing I did was to make my two cousins a present of as much of the counthry as they tuk a fancy to. Pat Carroll went down South, an’ he measured out a two big thracts of land, an’ called ’em North and South Carrollina; and Mick Egan went a bit in from the coast an’ measured out another slice an’ called it Michael Egan; but the darkeys, I hear, shortened that to Michegan.”

“An’ what did you do for the cabin boy?”

“To tell you the thruth,” says Andy, “I didn’t like to make a king of him, or give him a big thract of counthry, on account of his not bein’ an Irishman; but I made him a present of the first land we sighthed; an’ being a smart lad he tuk what he could get wud a good grace an’ detarmined to make the most of his little slice. He’s goin’ to build a lighthouse on it shortly, an’ charge a toll to the ships that pass; an’ I have no manner of doubt he’ll pick up a good livin’ at ‘Sandy Hook,’ for he’s a knowin’ young shaver.”

[Pg 27]

“Did you bring the wife home wud you?” axed King Cormac.

“Not this thrip,” says Andy. “I got her to laive her measure for a dhress, an’ ’twasn’t finished by the time I had to come away.”

“She’s black of coorse?” says King Cormac.

“Black as the ace of spades,” says Andy; “but I’m towld she’ll bleach in the sun, an’ even if she don’t turn the right colour,” says he, “sure I can give her an odd coat of whitewash now an’ again.”

“You haven’t towld me what sort of a counthry it is,” says King Cormac; “maybe ’tis all bog.”

“Bog!” says Andy, curlin’ his lip. “There isn’t a bit of bog land in it from Aist to West.”

“An’ what do they grow in it?” says King Cormac.

“Everything,” says Andy; “but mostly goold nuggets.”

“What!” says King Cormac, startin’ up out of his aisy chair.

“No wondher you’re astonished,” says Andy.

“Goold nuggets!” says the King of Munsther.

[Pg 28]

“Ay,” says Andy, “’tis rotten wud ’em the counthry is. I wint out to the diggin’s,” says he, “an’ there’s as much goold in wan field there as ’ud build the Rock of Cashel twice over.”

“Murdher alive!” says the King; “’tis a great place intirely it must be! But what is it you want a poor sthrugglin’ man like me to do for you, Andy?”

“Not much,” says Andy, “but little as it is it manes a dale to me. You see the goold is no value at all at all in my counthry.”

“But sure you could bring a few cargoes of it over here?” says King Cormac.

“That’s the very thing I came to consult wud yerself about,” says Andy. “You see if I wor to bring a load of it into Cork harbour ’tis saised on it wud be, an’, I’ll go bail some of my neighbours ’ud be bla’guards enough to swear I didn’t come by it honest. Now here’s my offer to you, King Cormac,” says Andy. “I have no likin’ at all to be a king, especially wud nothing but a lot of tambourine-playin’ niggers for my subjects, an’ my proposal[Pg 29] to you this blessed mornin’ is to sell you the whole counthry for a hundred pound down on the nail, wud the perviso that I’m allowed to take as much goold out of it as me own little thrawler can carry, for I’m not a covechous man at all.”

“Will you give me that in writin’?” says King Cormac.

“Of coorse,” says Andy; “but there’s wan more condition.”

“What’s that?” says King Cormac.

“That you buys my cargo for the Mint,” says Andy.

“How much do you want for it?” says King Cormac.

“The market price,” says Andy.

“Will you take Griffith’s valuation,” says King Cormac, who was a hard hand at buyin’ or sellin’.

“Well, not to break your word, I will,” says Andy.

“Then it’s a bargain,” says King Cormac. “I’ll send for my head clerk, an’ we’ll dhraw up the agreement.”

[Pg 30]

So the head clerk of the coort was sint for, an’ he dhrew up a great long dockyment that ’ud cover the side of a barracks, an’ King Cormac and Andy signed their names at the fut of it.

“I’ll give you my dhraft on the Munsther Bank,” says King Cormac, “for the hundhred pound.”

“Will there be any charge for cashin’ it?” says Andy.

“No,” says King Cormac, “I’m always on the right side of the books there, an’ I’m a head directhor into the bargain.”

“Well, I’ll be sayin’ good-bye now,” says Andy, taking the dhraft from King Cormac; “an’ you may expect to hear of me again in or about three months’ time.”

“Howld on a bit!” says King Cormac. “When am I to enther into possession of the new counthry?”

“Whin I comes back, of coorse,” says Andy. “If I was to bring you over wud me now maybe the Injuns ’ud make some objections to my takin’ the[Pg 31] goold out of the counthry. ’Tis best to keep ’em in the dark for a spell about this bargain of ours. Maybe ’tis a rebellion they’d rise agen you if you wor to go over hot fut afther me, for they have their feelin’s, of coorse.”

“Of coorse,” says King Cormac. “But make your voyage as quick as you can, Andy, for ’tis dyin’ I am to take charge of this new counthry of mine.”

“I’ll be as quick as win’ and weather will permit,” says Andy; “an’ barrin’ accidents of navigation you may reckon on me, say, for this day three months. Good-bye now,” says he, givin’ King Cormac’s fist another hearty grip.

“Good-bye,” says King Cormac, “an’ a quick voyage to you, my sweet fellow!”

So Andy walked back to Cork an’ cashed the King’s dhraft on the bank, an’ thin he goes down to the quay an’ jumped aboord the thrawler.

“Up stick, boys!” says he to the crew. “We have just three months to do it, so ye’ll have to work purty hard an’ constant.”

[Pg 32]

Well, in three months to the very day Andy sails up Cork river wance more. His little craft was down to the scuppers in the wather, an’ seein’ her so deep the revenue boat pulls off an’ an officer jumps aboord.

“Where are you from?” axes the revenue man.

“We’re from New York,” says Andy.

“There’s no such a place,” says the revenue man.

“That only shows your ignorance,” says Andy.

“It isn’t down on the charts, anyhow,” says the revenue man, partly losin’ his timper.

“Of coorse it isn’t,” says Andy, “for ’twas only discovered by meself some months back.”

“Is that so?” says the revenue man. “An’ what’s the bearin’s of it?”

“That’s my saycrit,” says Andy.

“’Tis a dark man, you are!” says the revenue officer, who knew Andy well by sighth.

“You’re not the first that thought so,” says Andy.

[Pg 33]

“Have you any smuggled tobaccy aboord?” says the revenue man.

“Only what’s allowed for ship’s use on the voyage,” says Andy, answerin’ him back mighty independent.

“I see you knows the law,” says the revenue man.

“Purty fair,” says Andy.

“An’ what’s your cargo?” says the revenue man.

“Goold for the mint,” says Andy.

“Goold!” says the revenue man, nearly dhroppin’ wud surprise.

“Ay,” says Andy, “an’ very good goold it is too.”

“Where are you goin’ to land it?” says the revenue man.

“Wherever the King of Munsther ordhers me, for ’tis sowld to his own self. An’ look here,” says he, “I won’t have any meddlin’ wud my affairs. If you gives me the laste throuble or annoyance I’ll complain of you to King Cormac, an’ he’ll give[Pg 34] you your discharge purty quick, I can tell you, for he’s undher a heavy obligation to me.”

Begor the revenue man sung purty small after that, for he knew that King Cormac was quick in his timper, an’ of coorse if Andy was to tell on him, maybe ’tis cut off his pinsion the King would as well as give him his discharge. So he says to Andy in a frindly way, “Well, I’ll put a man in charge if you have no objections. ’Twill keep the quay boys off at any rate, Andy, if they sees a man wud a gun aboord.”

“Very well,” says Andy. “Only let it be undherstood that I’ve left ordhers wud my cousin, Pat Carroll, to hang any wan from the yardarm by martial law who attimpts to meddle wud the cargo.”

“I suppose you’re goin’ straight to the Rock of Cashel now,” says the revenue man, seein’ Andy takin’ off his sou’westher and fixin’ a top hat on his head.

“I am,” says Andy.

“You might put in a good word for me wud the King,” says the revenue man.

[Pg 35]

“I’ll wait till I comes back,” says Andy; “an’ if I hears a good account of your man from Pat Carroll, I’ll sartinly see that your wages is raised.”

“More power to your elbow!” says the revenue man. “Let me give you a leg over the side,” says he.

So Andy stepped over the rail and dhropped into a small boat that landed him safe and sound on the quay, an’ then he started to thramp it again to the Rock of Cashel. The sinthry knew him this time an’ let him in at wance, and Andy walked up the steps of the Rock an’ knocked at the dhrawin’-room door.

“Come in,” says King Cormac, so in Andy wint.

“Well, here I am again,” says he, “thrue to my promise. I know I’m a few days behind time, but there was a nasty slop of a say outside for the past forty-eight hours, an’ I was rather in dhread of makin’ for the enthrance of the harbour.”

“You worn’t in dhread of makin’ sail out of the[Pg 36] enthrance of the Shannon the day before yestherday,” says King Cormac, lookin’ hard at Andy.

“What do you mane?” says Andy, turnin’ rather white in the gills.

“Nothing,” says King Cormac. “Only a joke.”

“’Tis a quare way of jokin’ you have,” says Andy.

“Maybe,” says King Cormac, who seemed very short in his conversation this mornin’.

“I brought the cargo of goold,” says Andy.

“Did you?” says the King. “An’ did you bring the wife? for I’m rather anxious to see wan of my new subjects.”

“Well,” says Andy, an’ there was a kind of a stammer in his voice, “I brought her right enough, but I landed the poor girl at Roche’s Point, for she was mortial say-sick on the voyage.”

“Thin, I can see her of coorse?” says King Cormac.

“You can,” says Andy, “as soon as she gets the rowl of the westhern ocean out of her head.”

[Pg 37]

“’Tis a puzzlin’ business altogether,” says the King half to himself. “Look here, Andy,” says he, “I may as well tell you the honest thruth, for I don’t like to condimn a man wudhout givin’ him a fair chance. There’s a sayrious charge brought agen you this week.”

“I wouldn’t be at all surprised at that,” says Andy. “I towld you long ago that the neighbours wor never tired of backbitin’ me.”

“’Tisn’t a neighbour this time,” says the King. “’Tis a Portingale man.”[1]

“Yerrah!” says Andy, “sure a king of your parts wouldn’t believe the daylight from a Portingale man!”

“That depinds,” says King Cormac.

“An’ what does the bla’guard say agen me?” says Andy.

“I’ll tell you,” says the King; “an’ if you don’t disprove it I’ll hang you in chains as sure as my name is Cormac of Munsther.”

“That’s purty sure by all accounts,” says Andy,

[Pg 38]

thryin’ to show he took little heed of what any Portingale man could say about him; but he didn’t look much at his aise, I can tell you.

“Maybe ’tis laugh at the wrong side of your mouth you will before I’m done wud you,” says King Cormac; “an’ this is the charge agen you. Last week it seems you sailed into the Shannon—”

“I won’t deny it,” intherrupts Andy. “’Twas the first landin’ place I could get a grip of. I was run out of tobaccy an’ of salt pork, an’ I’m partial to Limerick twist an’ Limerick bacon.”

“Very well,” says the King. “Your acknowledgin’ the charge saves me the throuble of summonin’ eye-witnesses. Anyhow, in Limerick you wint into a public-house. Do you deny that?”

“I don’t,” says Andy; “nor I don’t deny I had a dhrop too much aither.”

“Very well,” says the King; “but you’re not obliged to make charges agen yerself. At any rate, this Portingale man saw you in this public house, an’ he recognized you at wance. It seems you boorded a ship he was sailin’ in some years[Pg 39] back, loaded wud a general cargo, an’ afther murdherin’ all aboord you tuk away the valuable part of this cargo, amongst which wor a lot of bags of Portingale goold.”

“That’s a quare story, sure enough,” says Andy. “Now if I murdhered every wan aboard, how could this fellow you’re spaykin’ of be in Limerick last week?”

“He was in hidin’ in the lazareet,” says the King, “an’ that’s how you missed him.”

Begor Andy didn’t look at all well whin he heard this, but he was a desperate darin’ man, an’ says he, “I know what you’re dhrivin’ at, King Cormac. You mane to make out that ’tis a pirate I am, an’ that the story I towld you about the great new counthry is only moonshine.”

“Exactly,” says King Cormac.

“’Tis aisy to disprove that, at any rate,” says Andy. “If any of my prisent cargo is in Portingale money, or in the money of any counthry known to the prisent generation, I’ll give you laife to hang draw an’ quarther me before mornin’.”

[Pg 40]

“Do you take me for an omadhaun?” says King Cormac. “Do you think I never heard of a meltin’-pot?”

Andy was silent for a spell afther that remark, an’ whin he spoke again there was a sthrange hoarseness in his voice. “I see,” says he, “that things look black agen me, but for all that I can clear myself if I only gets a fair chance.”

“I’ll give you every chance in the world,” says King Cormac.

“Look at here!” says Andy, “If I shows you my black-skinned wife will you believe me?”

“I will,” says King Cormac; “but I’ll take care you don’t make a hare of me this time. I’ll put three armed revenue men in the thrawler, an’ I’ll see that every weapon is taken from your boat, an thin you can sail down to Roche’s Point an’ bring me back your wife; an’ mind you,” says King Cormac, “’twon’t do to thry an’ desayve me by coatin’ wan of my own subjects wud gas tar, for I’ll have the coort physician to examine the woman—that is if you brings her here. An’ if you don’t[Pg 41] bring her,” says he, “take my word for it I’ll hang you in chains from the top of the Rock.”

Faith, Andy saw the King was in fair airnest, so he never said a word more, but allowed himself to be taken down to Cork undher a sthrong escort. His thrawler was examined carefully an’ all the weapons wor taken out of her, an’ three armed men wor put aboord.

’Twas nigh dusk when they started the fishin’-boat from the quay of Cork, an’ the win’ rose to a gale before they got abreast of Grab-all Bay. The revenue men implored Andy to put into the Bay for shelter or to run back to Queenstown, but he persuaded ’em to let him continue his journey. “No say nor win’ was ever a match for me,” says he; “an’ I can steer my craft through the eye of a needle.”

An’, sure enough, ’twas a wondherful hand at the tiller he was. Every big lump of a say that threatened to swamp the little boat Andy dodged as aisy as children dodge wan another at blindman’s-buff; but for all that the revenue men wor[Pg 42] ready to die of the fright. At last the thrawler was nearly abreast of Roche’s Point, an’ the say was rowlin’ in mountains high, an’ the win’ was roarin’ loud enough to burst the dhrum of your ear.

“Study now!” shouts Andy, an’ his voice was heard clear above the tundher of the gale an’ the say. “Study!” he shouts again; “an’ say your last prayer quick, for this minute we die!”

An’ as he said the words he gripped the tiller in his two fists an’ sent the thrawler’s head right into the mouth of the biggest say that ever rowled into Cork harbour; an’ under she went, goold an’ all an’ rose no more.

To this day they’re many that believe Andy Merrigan discovered the New World; an’ faix if he didn’t ’tis sthrange enough that generations afterwards when Columbus ventured across the Atlantic he found the place called afther Andy, and parts of it afther his crew. At any rate, of a winther’s night whin the sky is heavy an’ the win’[Pg 43] is high, the people from Roche’s Point will tell you they see the thrawler sthrugglin’ in the trough of an angry say, an’ loudher than the sounds of the elements is heard the last shout of Andy Merrigan an’ the terrible cry of the six hands that wint down wud him.

[Pg 44]

[1] “Portingale man” is Anglo-Hibernian for “Portuguese.”

Wance upon a time, an’ a very good time it was too, there was a dacent little man, named Paddy Power, that lived in the parish of Portlaw.

At the time I spake of, an’ indeed for a long spell before it, most of Paddy’s neighbours had wandhered from the thrue fold, an’ the sheep that didn’t stray wor, not to put too fine a point on it, a black lot. But Paddy had always conthrived to keep his last end in view, an’ he stuck to the ould faith like a poor man’s plasther.

Well, in the coorse of time poor Paddy felt his days wor well-nigh numbered, so he tuk to the bed an’ sent for the priest; an’ thin he settled himself down to aise his conscience an’ to clear the road in the other world by manes of a good confession.

He reeled off his sins, mortial an’ vaynial, to the priest by the yard, an’ begor he felt mighty [Pg 45]sorrowful intirely whin he thought what a bad boy he’d been an’ what a hape of quare things he’d done in his time—though, as I’ve said before, he was a dacent little man in his way, only, you see, bein’ so close to the other side of Jordan, he tuk an onaisy view of all his sayin’s and doin’s. Poor Paddy—small blame to him—was very aiger to get a comfortable corner in glory in his old age, for he’d a hard sthruggle enough of it here below.

Well, whin he’d towld all his sins to Father McGrath, an’ whin Father McGrath had given him a few hard rubs by way of consolation, he bent his head to get the absolution, an’, lo an’ behold you! before the priest could get through the words that would open the gates of glory to poor Paddy the life wint out of the man’s body.

It seems ’twas a busy mornin’ in heaven, an’ as soon as Father McGrath began to say the first words of the absolution, down they claps Paddy Power’s name on the due-book.—However, we’ll come to that part of the story by an’ by.

Anyhow, up goes Paddy, an’ before he knew[Pg 46] where he was he found himself standin’ outside the gates of Paradise. Of coorse, he partly guessed there ’ud be throuble, but he thought he’d put a bowld face on, so he gives a hard double-knock at the door, an’ a holy saint shoves back the slide an’ looks out at him through an iron gratin’.

“God save all here!” says Paddy.

“God save you kindly!” says the saint.

“Maybe I’m too airly?” says Paddy, dhreadin’ all the time that ’tis the cowld showlder he’d get.

“’Tis naither airly nor late here,” says the saint, “pervidin’ you’re on the way-bill. What’s yer name?” says he.

“Paddy Power,” says the little man from Portlaw.

“There’s so many of that name due here,” says the saint, “that I must ax you for further particulars.”

“You’re quite welcome, your reverence,” says Paddy.

“What’s your occupation?” says the saint.

[Pg 47]

“Well,” says Paddy, “I can turn my hand to anything in raison.”

“A kind of Jack-of-all-thrades?” says the saint.

“Not exactly that,” says Paddy, thinkin’ the saint was thryin’ to make fun of him. “In fact,” says he, “I’m a general dayler.”

“An’ what do you generally dale in?” axes the saint.

“All’s fish that comes to my net,” says Paddy, thinkin’ of coorse ’twould put Saint Pether in good humour to be reminded of ould times.

“An’ is it a fisherman you are, thin?” axes the saint.

“Well, no,” says Paddy, “though I’ve done a little huckstherin’ in fish in my time; but I was partial to scrap iron, as a rule.”

“To tell you the thruth,” says the saint, “I’m not over fond of general daylin’, but of coorse my private feelin’s don’t intherfere wud my duties here. I’m on the gates agen my will for the matther of that; but that’s naither here nor there so far as yourself is consarned, Paddy,” says he.

[Pg 48]

“It must be a hard dhrain on the constitution at times,” says Paddy, “to be on the door from mornin’ till night.”

“’Tis,” says the saint, “of a busy day—but I must go an’ have a look at the books. Paddy Power is your name?” says he.

“Yis,” says Paddy; “an’, though ’tis meself, that says it, I’m not ashamed of it.”

“An’ where are you from?” axes the saint.

“From the parish of Portlaw,” says Paddy.

“I never heard tell of it,” says the saint, bitin’ his thumb.

“Sure it couldn’t be expected you would, sir,” says Paddy, “for it lies at the back of God-speed.”

“Well stand there, Paddy avic,” says the holy saint, “an’ I’ll have a good look at the books.”

“God bless you!” says Paddy. “Wan ’ud think ’twas born in Munsther you wor, Saint Pether, you have such an iligant accent in spaykin’.”

Faix, Paddy was beginnin’ to dhread that his name wouldn’t be found on the books at all on account of his not havin’ complate absolution, so he[Pg 49] thought ’twas the best of his play to say a soft word to the keeper of the kays.

The saint tuk a hasty glance at the enthry-book, but when Paddy called him Saint Pether he lifted his head, an’ he put his face to the wicket again, an’ there was a cunnin’ twinkle in his eye.

“An’ so you thinks ’tis Saint Pether I am?” says he.

“Of coorse, your reverence,” says Paddy; “an’ ’tis a rock of sense I’m towld you are.”

Well, wud that the saint began to laugh very hearty, an’ says he,—

“Now it’s a quare thing that every wan of ye that comes from below thinks Saint Pether is on the gates constant. Do you ralely think, Paddy,” says he, “that Saint Pether has nothing else to do, nor no way to pass the time except by standin’ here in the cowld from year’s end to year’s end, openin’ the gates of Paradise?”

“Begor,” says Paddy, “that never sthruck me before, sure enough. Of coorse he must have some sort of divarsion to pass the time. An’ might I[Pg 50] ax your reverence,” says he, “what your own name is, an’ I hopes you’ll pardon my ignorance.”

“Don’t mintion that,” says the saint; “but I’d rather not tell you my name, just yet at any rate, for a raison of my own.”

“Plaize yourself an’ you’ll plaize me, sir,” says Paddy.

“’Tis a civil-spoken little man you are,” says the saint.

Findin’ the saint was such a nice agreeable man an’ such an iligant discoorser, Paddy thought he’d venture on a few remarks just to dodge the time until some other poor sowl ’ud turn up an’ give him the chance to slip into Paradise unbeknowst—for he knew that wance he got in by hook or by crook they could never have the heart to turn him out of it again. So says he,—

“Might I ax what Saint Pether is doin’ just now?”

“He’s at a hurlin’ match,” says the deputy.

“Oh murdher!” says Paddy, “couldn’t I get a peep at the match while you’re examinin’ the books?”

[Pg 51]

“I’m afeard not,” says the saint, shakin’ his head. “Besides,” says he, “I think the fun is nearly over by this time.”

“Is there often a hurlin’ match here?” axes Paddy.

“Wance a year,” says the saint. “You see,” says he, pointin’ over his showldher wud his thumb, “they have all nationalities in here, and they plays the game of aich nation on aich pathron saint’s day, if you undherstand me.”

“I do,” says Paddy. “An’ sure enough ’twas Saint Pathrick’s Day in the mornin’ whin I started from Portlaw, an’ the last thing I did—of coorse before tellin’ my sins—was to dhrink my Pathrick’s pot.”

“More power to you!” says the saint.

“I suppose Saint Pathrick is the umpire to-day?” says Paddy.

“No,” says the saint. “Aich of us, you see, takes our turn at the gates on our own festival days.”

“Holy Moses!” shouts Paddy. “Thin ’tis to[Pg 52] Saint Pathrick himself I’ve been talkin’ all this while back. Oh murdher alive, did I ever think I’d live to see this day!”

Begor the poor augashore of a man was fairly knocked off his head to discover he was discoorsin’ so fameeliarly wud the great Saint Pathrick, an the great saint himself was proud to see what a dale the little man from Portlaw thought of him; but he didn’t let on to Paddy how plaized he was. “Ah!” says he, “sure we’re all on an aiquality here. You’ll be a great saint yourself, maybe, wan of these days.”

“The heavens forbid,” says Paddy, “that I’d dhrame of ever being on an aiquality wud your reverence! Begor ’tis a joyful man I’d be to be allowed to spake a few words to you wance in a blue moon. Aiquality inagh!” says he. “Sure what aiquality could there be between the great apostle of Ould Ireland and Paddy Power, general dayler, from Portlaw?”

“I wish there was more of ’em your way of thinkin’, Paddy,” says Saint Pathrick, sighin’ deeply.

[Pg 53]

“An’ do you mane to tell me,” says Paddy, “that any craychur inside there ’ud dare to put himself on an aiqual footin’ wud yourself?”

“I do, thin,” says Saint Pathrick; “an’ worse than that,” says he, “there’s some of ’em thinks ’tis very small potatoes I am, in their own mind. I gives you me word, Paddy, that it takes me all my time occasionally to keep my timper wud Saint George an’ Saint Andhrew.”

“Bad luck to ’em both!” says Paddy, intherruptin’ him.

“Whisht!” says Saint Pathrick. “I partly admires your sentiments, but I must tell you there’s no rale ill-will allowed inside here. You’ll feel complately changed wance you gets at the right side of the gate.”

“The divil a change could make me keep quiet,” says Paddy, “if I heard the biggest saint in Paradise say a hard word agen you, or even dar’ to put himself on a par wud you!”

“Oh, Paddy!” says Saint Pathrick, “you mustn’t allow your timper to get the betther of[Pg 54] you. ’Tis hard, I know, avic, to sthruggle at times agen your feelin’s, but the laiste said the soonest mended.”

“An’ will I meet Saint George and Saint Andhrew whin I get inside?”

“You will,” says Saint Pathrick; “but you mustn’t disgrace our counthry by makin’ a row wud aither of ’em.”

“I’ll do my best,” says Paddy, “as ’tis yourself that axes me. An’ is there any more of ’em that thrates you wud contimpt?”

“Well, not many,” says Saint Pathrick. “An’ indeed,” says he, “’tis only an odd day we meets at all; an’ I can tell you I’m not a bad hand at takin’ my own part—but there’s wan fellow,” says he, “that breaks my giddawn intirely.”

“An’ who is he? the bla’guard!” says Paddy.

“He’s an uncanonized craychur named Brakespeare,” says Saint Pathrick.

“A wondher you’d be seen talkin’ to the likes of him!” says Paddy; “an’ who is he at all?”

[Pg 55]

“Did you never hear tell of him?” says Saint Pathrick.

“Never,” says Paddy.

“Well,” says Saint Pathrick, “he made the worst bull—”

“Thin,” says Paddy, intherruptin’ him in hot haste, “he’s wan of ourselves—more shame for him! O wait till I gets a grip of him by the scruff of the neck!”

“Whisht! I tell you!” says Saint Pathrick. “Perhaps ’tis committin’ a vaynial sin you are now, an’ if that wor to come to Saint Pether’s ears, maybe he’d clap twinty years of Limbo on to you—for he’s a hard man sometimes, especially if he hears of any one losin’ his timper, or getting impatient at the gates. An’ moreover,” says Saint Pathrick, “himself an’ this Brakespeare are as thick as thieves, for they both sat in the same chair below. I had a hot argument wud Nick yesterday.”

“Ould Nick, is it?” says Paddy.

“No,” says Saint Pathrick laughin’. “Nick[Pg 56] Brakespeare, I mane—the same indeveedual I was tellin’ you about.”

“I beg your reverence’s pardon,” says Paddy, “an’ I hopes you’ll excuse my ignorance. But you wor goin’ to give me an account of this hot argument you had wud the bla’guard whin I put in my spoke.”

Begor Saint Pathrick dhrew in his horns thin, an’ fearin’ Paddy might think they wor in the habit of squabblin’ in heaven he says, “Of coorse, I meant only a frindly discussion.”

“An’ what was the frindly discussion about?” axes Paddy.

“About this bull of his,” says Saint Pathrick.

“The mischief choke himself an’ his cattle!” says Paddy.

“Begor,” says Saint Pathrick, “’twas choked the poor man was, sure enough.”

“More power to the man that choked him!” says Paddy. “I hopes ye canonized him.”

“’Twasn’t a man at all,” says Saint Pathrick.

“A faymale, perhaps?” says Paddy.

[Pg 57]

“Fie, fie, Paddy,” says Saint Pathrick. “Come, guess again.”

“Ah, I’m a poor hand at guessin’,” says Paddy.

“Well, ’twas a blue bottle,” says Saint Pathrick.

“An’ was it thryin’ to swallow the bottle an’ all he was?” says Paddy. “He must have been ‘a hard case.’”

Begor Saint Pathrick burst out laughin’, an’ says he, “You’ll make your mark here, Paddy, I have no doubt.”

“I’ll make my mark on them that slights your reverence, believe me,” says Paddy.

“Hush!” says Saint Pathrick, puttin’ his finger on his lips an’ lookin’ very solemn an’ business-like. “Here comes Saint Pether,” he whispers, rattlin’ the kays to show he was mindin’ his duties. “He looks in good-humour too; so it’s in luck you are.”

“I hope so, at any rate,” says Paddy; “for the clouds is very damp, an’ I’m throubled greatly wud the rheumatics.”

“Well, Pathrick,” says Saint Pether, comin’ up to the gates—Paddy Power could just get a sighth[Pg 58] of the pair inside through the bars of the wicket—“how goes the inemy? Have you had a hard day of it, my son?”

“A very hard mornin’,” says Saint Pathrick. “They wor flockin’ here as thick as flies at cock-crow—I mane,” says he, gettin’ very red in the face, for he was in dhread he was afther puttin’ his fut in it wud Saint Pether, “I mane just at daybreak.”

“It’s strange,” says Saint Pether, in a dhramey kind of a way, “but I’ve noticed meself that there’s often a great rush of people in the early mornin’: often I don’t know whether it’s on my head or my heels I do be standin’ wud the noise they kicks up outside, elbowin’ wan another, an’ bawlin’ at me as if it was hard of hearin’ I was.”

“How did the match go?” says Saint Pathrick, aiger to divart Saint Pether’s mind from his throubles.

“Grand!” says Saint Pether, brightenin’ up. “Hurlin’ is a great game. It takes all the stiffness out of my ould joints. But who’s that outside?” catching sighth of Paddy Power.

[Pg 59]

“A poor fellow from Ireland,” says Saint Pathrick.

“I dunno how we’re to find room for all these Irishmen,” says Saint Pether, scratchin’ his head. “’Twas only last week I gev ordhers to have a new wing added to the Irish mansion, an’ begor I’m towld to-day that ’tis chock full already. But of coorse we must find room for the poor sowls. Did this chap come viâ Purgathory?” says he.

“No,” says Saint Pathrick. “They sint him up direct.”

“Who is he” says Saint Pether.

“His name is Paddy Power,” says St. Pathrick, “He seems a dacent sort of craychur.”

“Where’s he from?” axes Saint Pether.

“The Parish of Portlaw,” says Saint Pathrick.

“Portlaw!” says Saint Pether. “Well, that’s sthrange,” says he, rubbin’ his chin. “You know I never forgets a name, but to my sartin knowledge I never heard of Portlaw before. Has he a clane record?”

“There’s a thrifle wrong about it,” says Saint[Pg 60] Pathrick. “He’s down on the way bill, but there are some charges agen him not quite rubbed out.”

“In that case,” says Saint Pether, “we’d best be on the safe side, an’ sind him to Limbo for a spell.”

Begor when Paddy Power heard this he nearly lost his seven sinses wud the fright, so he puts his face close up to the wicket, an’ he cries out in a pitiful voice,—

“O blessed Saint Pether, don’t be too hard on me. Sure even below, where the law is sthrict enough agen a poor sthrugglin’ boy, they always allows him the benefit of the doubt, an’ I gives you my word, yer reverence, ’twas only by an accident the slate wasn’t rubbed clane. I know for sartin that Father McGrath said some of the words of the absolution before the life wint out of my body. Don’t dhrive a helpless ould man to purgathory, I beseeches you. Saint Pathrick will go bail for my good behaviour, I’ll be bound; an’ tis many the prayer I said to your own self below!”

[Pg 61]

Faix, Saint Pether was touched wud the implorin’ way Paddy spoke, an’ turnin’ to Saint Pathrick he says, “’Tis a quare case, sure enough. I don’t know that I ever remimber the like before, an’ my memory is of the best. I think we’d do right to have a consultation over the affair before we decides wan way or the other.”

“Ah give the poor angashore a chance,” says Saint Pathrick. “’Tis hard to scald him for an accident. Besides,” says he, brightenin’ up as a thought sthruck him, “you say you never had a man before from the parish of Portlaw, an’ I remember you towld me wance that you’d like to have a represintative here from every parish in the world.”

“Thrue enough,” says Saint Pether; “an maybe I’d never have another chance from Portlaw.”

“Maybe not,” says Saint Pathrick, humourin’ him.

So Saint Pether takes a piece of injy-rubber from his waistcoat pocket, an’ goin’ over to the[Pg 62] enthry-book he rubs out the charges agen Paddy Power.

“I’ll take it on meself,” says he, “to docthor the books for this wance, only don’t let the cat out of the bag on me, Pathrick, my son.”

“Never fear,” says Saint Pathrick. “Depind your life on me.”

“Well, it’s done, anyhow,” says Saint Pether, puttin’ the injy-rubber back into his pocket; “an’ if you hands me over the kays, Pat,” says he, “I’ll relase you for the day, so that you can show your frind over the grounds.”

“’Tis a grand man you are!” says Saint Pathrick. “My blessin’ on you, avic!”

“Come in, Paddy Power,” says Saint Pether, openin’ the gates; “an’ rimember always that you wouldn’t be here for maybe nine hundred an’ ninety-nine year or more only that you’re the only offer we ever had from the Parish of Portlaw.”

[Pg 63]

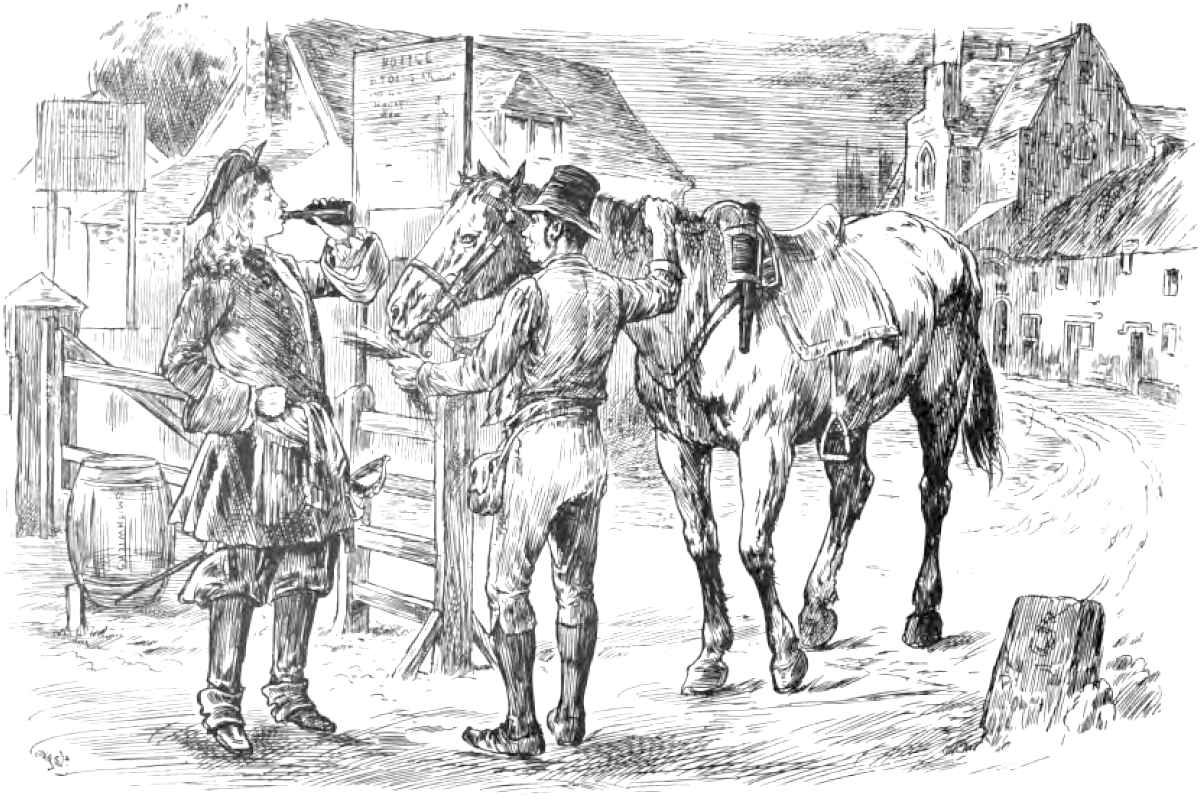

I suppose it’s well known that King John made two visits to the city of Watherford. The first time he came he was only a slip of a boy of about nineteen year, an’ his father, who had a hard job rearin’ him (for ’tis the unmannerdly young cub he was) thought he’d kill two birds wud wan stone by gettin’ rid of the prince for a short spell in the first place, an’ by gettin’ the boy to make himself frindly wud the Irish chiefs in the second place.

But nothin’ would suit young Masther John except divarsion an’ bla’guardin’. The moment he put his fut on Irish soil he began to poke fun at the ould chieftains’ beards. ’Twas jealous the young jackanapes was of the fine hairy faces of the crowd that met him on the quay of Watherford, for divil a hair he could grow on the upper part of[Pg 64] his lip, though he was near dhraggin’ the English coort into bankruptcy wud the quantities of bears’ grease an’ other barbers’ thricks he thried day afther day to coax out even a few morsels of a moustache.

Anyhow he made naither a good beginnin’ nor a good endin’ on his first thrip to Ireland. He ate so much fresh salmon that a rash broke out on him, an’ nearly dhrove him to despair, for he was fond of the faymales, an’ a man wud a bad rash even if he’s a prince of the blood isn’t the soort of craychur to make much headway wud the girls.

He got over the rash, however, in due coorse; an’ built an hospital in mimory of his recovery; an’ to this day it stands there at the fut of John’s Hill, an’ is called the “Leper Hospital.”

As soon as he got well rid of the rash, he began to make ructions in the counthry, kickin’ out the rale ould anshant owners of the soil, an’ makin’ presents of what didn’t belong to him to his own follyers. Begor even owld Henery, the father, got unaisy at[Pg 65] the son’s plan of campaign, so back he calls Prince John an’ puts a Misther Decoorcy in his place.

Well, time passed on, an’ when his call came, ould Henery the Second wint to Limbo; an’ afther a spell, the son John got a howld of the throne. He had always a hankerin’ for the Watherford salmon, even afther the rash it broke out on him, so as soon as he could make things snug in the English coort, away he sails again for Ireland.

This time of coorse he was a full king, an’ as he was several years ouldher, the Watherford people naaturally expected his manners would have improved; so they made up their minds to forget the thricks an’ bla’guardin’ of the nineteen year ould prince, an’ to give King John a hearty welcome.

When the Mayor an’ Corporation heard the news that the royal barge was comin’ up the river, they put on their grand robes and started down the quay. They wint outside the walls a bit until they came to a piece of slob land near the mouth of a sthrame, an’ there they stud up to[Pg 66] their ankles in slush until the king’s ship hove in sighth. Thin they waved a flag of welcome to his Majesty, who was standin’ on deck, an’ bawled out to him to dhrop anchor abreast of them. So the captain—a red-whiskered Welshman who chawed more tobaccy than was wholesome for him—puts the ship’s head in for the shore, an’ dhropped anchor as soon as he got close to the slob where the Mayor and Corporation wor standin’.

“How are we to get ashore, boys?” says King John, makin’ a foghorn of his fists.

“Aisy, avic,” says the Mayor. “It’s a sthrong ebb tide now, an’ if you’ll go below into your cabin the ship will dhry while your clanein’ your face an’ hands an’ fixin’ the crown on your poll.”

“All right,” says King John. “Come aboord as soon as the tide laives her.”

“I will,” says the Mayor.

Wud that King John went down to the cabin, an’ in about half an hour the ship began to ground an’ very soon afther the Mayor, not heedin’ the[Pg 67] sighth of a fut or two of wather between him an’ the king’s craft, made a start to go down to her.

“Howld on there, where ye are,” says he to the Corporation. “If ye was all to come aboord maybe ’tis heel over the little vessel would, for she looks a crank piece of goods.”

“All right,” says the Corporation. “We’ll wait here till you return, an’ a safe journey to your worship!”

Well, whin the Mayor got on deck of coorse his boots were dhrippin’ wud mud an’ wather.

“Is there a door-mat aboord?” says he to the skipper.

“Divil a wan,” says the skipper. “Do you think ’tis in a lady’s chamber you are?”

“You’re an unmannerdly lot,” says the Mayor, stampin’ on the decks an’ givin’ a kick out wud his left leg to shake some of the water out of his boot.

Just at that moment up comes King John from the cabin, an’ a few spatthers of mud went into his royal eye.

[Pg 68]

Before the Mayor could open his mouth to ax pardon the King bawls out at him, “What the mischief do you mane, you lubber? Will nothin’ plaize you only knockin’ the sighth out of my eyes an’ dirtyin’ my decks wud your muddy say-boots? ’Tis more like a mud-lark than a Mayor you are.”

The poor Mayor very nearly lost his timper intirely at the insultin’ words of King John, for ’twas none of his fault that he dirtied the decks, but he managed to conthrol himself, an’ says he, “I ax your majesty’s pardon for bringing the mud aboord, but might I make so bowld as to inquire how I could be expected to have clane boots afther thrampin’ through the slush out there. An’ as for knockin’ the sighth out of your eyes,” says he, “I give you me word I never seen you comin’ up the cabin stairs or I wouldn’t have lashed out wud my leg.”

“Give me none of your lip,” says the King. “I’d cut your ugly sconce off if I thought there was an atom of thraison in your mind.”

[Pg 69]

“Thraison!” says the Mayor, mighty indignant, for ’tis a proud soort of a man he was in his way. “I don’t know the maynin’ of the word.”

“I’ll soon tache you the maynin’ of it, you spalpeen,” says the King; “an’ if you don’t go down on your bended knees an’ beg my pardon this minute, an’ give me your note of hand for five hundred pound I’ll dhraw your teeth first for you, an’ thin I’ll thry you for thraison, wud meself for judge and jury, as soon as I sets fut in the city.”

The mischief only knows what would have happened thin only for a chum of the King’s who came up from the cabin at that minute.

“Your Majesty,” says the young lord, “I think, with all due respects to you, you’re too hard agen the Mayor. Sure the poor man did his best. He came aboord at the risk of gettin’ a heavy cowld in his head, in ordher to give you an airly welcome, an’ how could he mane thraison when he ran such a risk to sarve you?”

“Maybe you’re right,” says King John, who[Pg 70] owed the young lord a big lump of money and was partial to him for other raisons too. “Maybe you’re right; an’ I know,” says he, “that my timper is none of the best; and moreover the say-sickness isn’t out of my stomach yet, bad luck to it! All right,” says he, turnin’ to the Mayor, an’ spittin’ on his fist. “Put it there,” says King John, howldin’ out his hand.

So the Mayor spit in his own fist, an’ the pair shuk hands quite cordial.

All would have gone well then but for the iligant beard an’ whiskers the Mayor wore. The sighth of them fairly tormented King John, an’ the bla’guard broke out in him again as he looked at his worship an’ saw him sthrokin’ the fine silky hairs which (savin’ your presence) nearly shut out the view of the honest man’s stomach.

“I’ll take me oath ’tis a wig,” says the King to himself; “an’ faith if the wig isn’t stuck mighty fast to his chin the tug I’ll give it will soon laive it in fragments on the deck.”

So the King goes over to the Mayor an’ purtended[Pg 71] to be admirin’ the beautiful goold chain his worship carried round his neck, an’ while a cat would be lickin’ her ear he gives the beard such an onmerciful dhrag that he tore a fistful of it clane out of the dacent man’s chin.

The Mayor set up a screech—an small blame to him—that you’d hear from this to Mullinavat, an’ begor the crowd ashore thought ’twas bein’ murdhered he was; so King John, fearin’ the Corporation might thry to sink himself an’ the ship if they knew he was afther damagin’ their mayor, thought ’twas the best of his play to knuckle undher at wance. He begs the Mayor’s pardon in a mortial funk, an’ says he to him, “We’d best be gettin’ ashore immajertly the both of us.”

The poor Mayor of coorse couldn’t afford to show timper agen a king, so brushin’ the scaldin’ tears off his cheek he made up his mind to pocket his pride; but at the same time says he to himself, “I’ll tache this unmannerdly cub a lesson before he’s many hours ouldher.”

[Pg 72]

“All right, your majesty,” says he, aloud, to the King, “I quite agrees wud you that ’tis betther the pair of us should go ashore at wance; but come here,” says he, takin’ King John to the bulwarks of the ship an’ pointin’ over the side. “Now I ax you,” says he, “how are you to get ashore wud at laiste a fut of wather inside the little vessel still, an’ fifty yards, more or less, of dirty soft mud forenenst you?”

Begor, the King seemed puzzled at this; but he knew there was no time to be lost, for the crowd ashore was beginnin’ to grow bigger, and it was aisy to see that throuble was brewin’, for a few of the quay boys were peltin’ an odd pavin’-stone at the ship. “I laive it to you, Misther Mayor,” says he; “but whatever you do, don’t keep me standin’ here in the cowld, for I have a wake chest, an’ my inside is complately out of ordher afther the voyage.”

“Begor!” says the Mayor, dodgin’ a box of a pavin’-stone that came aboord that minute, “I dunno what’s best to be done. You’d get your[Pg 73] death if you wor to thramp it ashore in them patent leather boots of yours. I’ll tell you what I’ll propose,” says he.

“That’s what I’m waitin’ for you to do,” says the King, intherruptin’ him; “an’ if you don’t be quick about it, maybe ’tis hot wud a stone I’ll be, an’ in that case,” says he, “’twill be me duty as a king to bombard the city wud cannon-balls. D’ye mind me now?” says he, beginnin’ to show timper agen.

“I do,” says the Mayor. “Sure, if you didn’t take the words out of my mouth, I was goin’ to say that I’d carry you safe ashore on my own two showldhers.”

“Very well,” says King John; “but if you wish for paice an’ quietness you’d betther stir your stumps quick, for I tell you I won’t stand here to be made a cockshot of by these Watherford bla’guards.”

“Come on, thin,” says the Mayor.

So wud that the sailors fixed what they calls a cradle, an’ a few frinds of the King lifted him up[Pg 74] on the showldhers of the Mayor, an’ down the pair wor lowered into the little wash of wather inside the ship.

“Howld a tight grip of me now,” says the Mayor, makin’ a start; “for ’tis an onsartin sort of a journey. There’s a dale of shifthin’ sands about here, an’ if I wor to make a false step or lose my bearin’s, maybe they’d never hear of your majesty again in England; p’raps ’tis swallyed up in the mud the pair of us ’ud be, an’ I have a heavy family dependin’ on me.”

“I’ll keep a study grip,” says the King; “an’ for your own sake, an’ the sake of your heavy family, I’d recommend you to pick your steps as if ’twas threadin’ on eggs you wor.”

“Never fear,” says the mayor. “Is the crown fixed firm on your head?”

“’Tis,” says King John.

“The raison I axed you,” says the Mayor, “is that I thought ’twas a thrifle too big for you. I noticed it wobblin’ about on your head afther you came up from the cabin.”

[Pg 75]

“Well, to tell you the thruth, an’ ’tisn’t often I do the like,” says the King, “I didn’t laive my measure for that crown; but I’ve rowled a sthrip of newspaper inside the rim of it, an’ it doesn’t fit at all bad now,” says he, shakin’ his head, an’ fixin’ an eye-glass into his eye.

“Did you buy it ready-made? pardon me for axin’,” says the Mayor.

“No,” says King John; “but it belonged to my big brother, Richard.”

“I’ve heard tell of him,” says the Mayor. “The ‘Lion Heart’ they called him, wasn’t it?”

“It was,” says King John; “but between yerself and meself”—for he was mighty jealous of his brother, an’ indeed, he hadn’t a good word to throw to a dog—“’twas a ‘thrick’ lion he tore the heart out of.”

“Is that so?” says the Mayor.

“’Tis,” says King John. “You see,” says he, “himself an’ Blondin wor great chums intirely, an’ Blondin bein’ a circus man—”

“I know,” intherrupted the Mayor. “He crossed[Pg 76] over the Falls of Niagry on a rope, didn’t he?”

“He did,” says King John. “’Tis round his neck I’d like to have had the rope, for ’tis an onaisey time of it he gave meself be rescuin’ my brother. I made sure they’d cooked his goose in that Austrian castle, but nothin’ would suit his chum Blondin, if you plaize, except whistlin’ some of his ould circus tunes outside the walls, until the King of Austria let him in. Well, Blondin brought in a thrick lion wud him that he used to be showin’ off at the fairs. ‘Look here,’ says he to the King of Austria, ‘that man you’re keepin’ down in the cellar is a match for a lion.’ ‘Prove it,’ says the King of Austria. ‘I will,’ says Blondin. ‘Well, take the muzzle off yer baste,’ says the King of Austria, ‘an’ let the pair of ’em have a fair stand-up fight; an’ if King Richard bates the lion I’ll give him his liberty.’ ‘Done!’ says Blondin; so wud that he brings the lion down into the cellar, an’ of coorse my brother knew ’twas only an ould painted jackass without a tooth in his head, so he[Pg 77] makes wan grab at the unfortunate animal an’ tore the heart clane out of him.”

“Oh, murdher!” says the Mayor. “An’ that’s why they call him the ‘Lion Heart,’ is it?”

“It is,” says King John.

“An’ what’s that they calls yerself?” says the Mayor, who knew well that King John didn’t like to be reminded of the nickname he was known undher in the English Coorts, an’ wanted to take a rise out of him on the quiet.

“I’ll tell you what, my bucko,” says King John, for he felt the Mayor all of a thremble undher him, an’ he knew it was smotherin’ a laugh in his sleeve he was, “I’ll tell you what, my bucko,” says he, “you’d betther give me none of your sauce. Only for the onnathural way I’m placed now, perched up here like a canary-bird, I’d soon let you know who you wor thryin’ to poke your fun at. D’ye mind me now?”

“Begonnies!” says the Mayor, “’tis no fun, I can tell you, to be endeavourin’ to get safe ashore wud such a precious load on me showlders. If[Pg 78] yer Majesty thinks ’tis for a lark I’m carryin’ you, let me tell you that you’re intirely mistaken. Oh murdher!” says he, dhroppin’ on wan knee, “but ’tis into a boghole we are!”

Of coorse he knew there wasn’t a boghole wudin a mile of him, but he wanted to divart the King’s mind from what he was afther sayin’ about his nickname, for ’tis in dhread he was that maybe he was carryin’ the joke too far.

“Boghole!” bawls the King, nearly jumpin’ out of his skin wud the fright. “Let me down, you scoundhrel,” says he. “I see now that ’tis a thraisonable plot you have agen me afther all. I wondhered why it was you worn’t makin’ a sthraight coorse for the firm shore.”

An’ sure enough the Mayor had gone a dale out of his road just in ordher to have a rise out of King John, to pay him off for havin’ given his beard the tug.

The pair of ’em wor now standin’ close to the mouth of the pill, an’ the mud all round was as soft as butthermilk, an’ the poor Mayor was more[Pg 79] than half-way up to his knees in it; but he knew every inch of the ground, an’ wasn’t in the laiste danger or dhread of himself of coorse, if King John fell from his showlders there ’ud be an end of him, for he’d rowl down into the wathers of the pill before the Mayor could have time to get a grip of him.

“Go straight for the shore this minute, I command you,” says the King.

The Mayor saw that his Majesty was in a fair rage, so he made up his mind not to play any more thricks on him but to make a short cut through the mud to the Corporation.

“Howld your grip now,” says he, givin’ the King a sudden hoist to straighten him on his back; an’ before the words wor well out of his mouth off tumbles King John’s crown an’ down it rowls into the pill.

“Oh murdher!” says the mayor, forgettin’ himself complately, an’ going to dhrop the King into the mud. “’Tis lost the crown is! There’s twenty fut of wather there if there’s an inch, an’ there[Pg 80] isn’t a diver on the face of the earth would take a headher into it, the wathers are that filthy!”

“What are you doin’, you ruffian?” screams the King, catchin’ a grip of the Mayor’s whisker wud wan hand an’ of the goold chain wud the other. “Dhrop me at the peril of your life, you onnathural mousther,” says he.

“An’ what about the crown?” says the Mayor, thryin’to take the King’s fist out of his whiskers.

“Let it go to Jericho!” says King John.

“’Twouldn’t be the first time ’twas there, anyhow” says the Mayor, who was fond of his joke.

“’Tis a quare man you are,” says King John, thryin’ to smother a laugh; “but go on, you bla’guard,” says he, “an’ put me on dhry land at wance, an’ no more of your thricks.”

“Never fear!” says the Mayor; “an’ I hopes we’re none the worst frinds afther all’s said an’ done.”

“None the worse,” says King John, “only we’ll be betther frinds as soon as you land me in a hard spot.”

[Pg 81]

So the Mayor put his best fut forward an’ in a few minutes himself an’ the King were shakin’ hands wud the Corporation.

“You’ll catch your death of cowld,” says the Mayor to King John, “if you stand there much longer wudout your crown. Have you any objection,” says he, “to wearin’ my hat for a spell until they have time to forge a new figure-head for you?”

“Not the laiste objection in life,” says King John, fixin’ the Mayor’s hat on his head. “But ’tis dhry work, shakin’ hands, boys,” says he, addhressin’ the crowd assembled on the quay; “so the sooner we shapes our coorse for the nearest shebeen the betther I’ll like it, at any rate.”

“Bravo!” says the Corporation, startin’ a procession wud King John at the head of ’em an’ a fife an’ dhrum band from Ballybricken follyin’ up in the rear.

Well, to cut a long story short, King John whin he was laivin’ Watherford made a present of his borrowed caubeen to the Corporation; an’ if you[Pg 82] doubts my word you can go down to the Town Hall any day an’ ax to see King John’s hat, an’ the Mayor’s secrethary will show you the self-same wan that King John got the loan of from the ould anshent Mayor—an’ a very dilapidated speciment of head gear it is too.

That’s the true story of how King John lost his crown in the wash of the Pill, as the little sthrame is called; an’ sure ’tis known as John’s Pill to this day.

[Pg 83]

It was a little before the dawn of a July mornin’ many year ago, when Jimmy Murphy, a thin, spare man that kept the enthrance gates of the bridge of Watherford, at the County Kilkenny side, was roused out of a sound sleep by a terrible clatther.

He jumped up off his bed an’ came out of the toll-house rubbin’ his eyes, an’ the first thing he caught a glimpse of was the flash of steel. There wasn’t much light in the sky, an’ it tuk little Jimmy the best part of a minute before he spied a horseman outside, who was runnin’ his swoord back and for’a’d along the bars of the gates just like a little scamp of a boy when he’s passin’ a set of railin’s wud a stick in his hand.

[Pg 84]

“Howld your row, will you?” shouts Jimmy at the horseman.