CANTO XXIII

IN silence and in solitude we went,

One first, the other following his steps,

As minor friars journeying on their road.

The present fray had turn'd my thoughts to muse

Upon old Aesop's fable, where he told

What fate unto the mouse and frog befell.

For language hath not sounds more like in sense,

Than are these chances, if the origin

And end of each be heedfully compar'd.

And as one thought bursts from another forth,

So afterward from that another sprang,

Which added doubly to my former fear.

For thus I reason'd: "These through us have been

So foil'd, with loss and mock'ry so complete,

As needs must sting them sore. If anger then

Be to their evil will conjoin'd, more fell

They shall pursue us, than the savage hound

Snatches the leveret, panting 'twixt his jaws."

Already I perceiv'd my hair stand all

On end with terror, and look'd eager back.

"Teacher," I thus began, "if speedily

Thyself and me thou hide not, much I dread

Those evil talons. Even now behind

They urge us: quick imagination works

So forcibly, that I already feel them."

He answer'd: "Were I form'd of leaded glass,

I should not sooner draw unto myself

Thy outward image, than I now imprint

That from within. This moment came thy thoughts

Presented before mine, with similar act

And count'nance similar, so that from both

I one design have fram'd. If the right coast

Incline so much, that we may thence descend

Into the other chasm, we shall escape

Secure from this imagined pursuit."

He had not spoke his purpose to the end,

When I from far beheld them with spread wings

Approach to take us. Suddenly my guide

Caught me, ev'n as a mother that from sleep

Is by the noise arous'd, and near her sees

The climbing fires, who snatches up her babe

And flies ne'er pausing, careful more of him

Than of herself, that but a single vest

Clings round her limbs. Down from the jutting beach

Supine he cast him, to that pendent rock,

Which closes on one part the other chasm.

Never ran water with such hurrying pace

Adown the tube to turn a landmill's wheel,

When nearest it approaches to the spokes,

As then along that edge my master ran,

Carrying me in his bosom, as a child,

Not a companion. Scarcely had his feet

Reach'd to the lowest of the bed beneath,

When over us the steep they reach'd; but fear

In him was none; for that high Providence,

Which plac'd them ministers of the fifth foss,

Power of departing thence took from them all.

There in the depth we saw a painted tribe,

Who pac'd with tardy steps around, and wept,

Faint in appearance and o'ercome with toil.

Caps had they on, with hoods, that fell low down

Before their eyes, in fashion like to those

Worn by the monks in Cologne. Their outside

Was overlaid with gold, dazzling to view,

But leaden all within, and of such weight,

That Frederick's compar'd to these were straw.

Oh, everlasting wearisome attire!

We yet once more with them together turn'd

To leftward, on their dismal moan intent.

But by the weight oppress'd, so slowly came

The fainting people, that our company

Was chang'd at every movement of the step.

Whence I my guide address'd: "See that thou find

Some spirit, whose name may by his deeds be known,

And to that end look round thee as thou go'st."

Then one, who understood the Tuscan voice,

Cried after us aloud: "Hold in your feet,

Ye who so swiftly speed through the dusk air.

Perchance from me thou shalt obtain thy wish."

Whereat my leader, turning, me bespake:

"Pause, and then onward at their pace proceed."

I staid, and saw two Spirits in whose look

Impatient eagerness of mind was mark'd

To overtake me; but the load they bare

And narrow path retarded their approach.

Soon as arriv'd, they with an eye askance

Perus'd me, but spake not: then turning each

To other thus conferring said: "This one

Seems, by the action of his throat, alive.

And, be they dead, what privilege allows

They walk unmantled by the cumbrous stole?"

Then thus to me: "Tuscan, who visitest

The college of the mourning hypocrites,

Disdain not to instruct us who thou art."

"By Arno's pleasant stream," I thus replied,

"In the great city I was bred and grew,

And wear the body I have ever worn.

but who are ye, from whom such mighty grief,

As now I witness, courseth down your cheeks?

What torment breaks forth in this bitter woe?"

"Our bonnets gleaming bright with orange hue,"

One of them answer'd, "are so leaden gross,

That with their weight they make the balances

To crack beneath them. Joyous friars we were,

Bologna's natives, Catalano I,

He Loderingo nam'd, and by thy land

Together taken, as men used to take

A single and indifferent arbiter,

To reconcile their strifes. How there we sped,

Gardingo's vicinage can best declare."

"O friars!" I began, "your miseries—"

But there brake off, for one had caught my eye,

Fix'd to a cross with three stakes on the ground:

He, when he saw me, writh'd himself, throughout

Distorted, ruffling with deep sighs his beard.

And Catalano, who thereof was 'ware,

Thus spake: "That pierced spirit, whom intent

Thou view'st, was he who gave the Pharisees

Counsel, that it were fitting for one man

To suffer for the people. He doth lie

Transverse; nor any passes, but him first

Behoves make feeling trial how each weighs.

In straits like this along the foss are plac'd

The father of his consort, and the rest

Partakers in that council, seed of ill

And sorrow to the Jews." I noted then,

How Virgil gaz'd with wonder upon him,

Thus abjectly extended on the cross

In banishment eternal. To the friar

He next his words address'd: "We pray ye tell,

If so be lawful, whether on our right

Lies any opening in the rock, whereby

We both may issue hence, without constraint

On the dark angels, that compell'd they come

To lead us from this depth." He thus replied:

"Nearer than thou dost hope, there is a rock

From the next circle moving, which o'ersteps

Each vale of horror, save that here his cope

Is shatter'd. By the ruin ye may mount:

For on the side it slants, and most the height

Rises below." With head bent down awhile

My leader stood, then spake: "He warn'd us ill,

Who yonder hangs the sinners on his hook."

To whom the friar: "At Bologna erst

I many vices of the devil heard,

Among the rest was said, 'He is a liar,

And the father of lies!'" When he had spoke,

My leader with large strides proceeded on,

Somewhat disturb'd with anger in his look.

I therefore left the spirits heavy laden,

And following, his beloved footsteps mark'd.

CANTO XXIV

IN the year's early nonage, when the sun

Tempers his tresses in Aquarius' urn,

And now towards equal day the nights recede,

When as the rime upon the earth puts on

Her dazzling sister's image, but not long

Her milder sway endures, then riseth up

The village hind, whom fails his wintry store,

And looking out beholds the plain around

All whiten'd, whence impatiently he smites

His thighs, and to his hut returning in,

There paces to and fro, wailing his lot,

As a discomfited and helpless man;

Then comes he forth again, and feels new hope

Spring in his bosom, finding e'en thus soon

The world hath chang'd its count'nance, grasps his crook,

And forth to pasture drives his little flock:

So me my guide dishearten'd when I saw

His troubled forehead, and so speedily

That ill was cur'd; for at the fallen bridge

Arriving, towards me with a look as sweet,

He turn'd him back, as that I first beheld

At the steep mountain's foot. Regarding well

The ruin, and some counsel first maintain'd

With his own thought, he open'd wide his arm

And took me up. As one, who, while he works,

Computes his labour's issue, that he seems

Still to foresee the' effect, so lifting me

Up to the summit of one peak, he fix'd

His eye upon another. "Grapple that,"

Said he, "but first make proof, if it be such

As will sustain thee." For one capp'd with lead

This were no journey. Scarcely he, though light,

And I, though onward push'd from crag to crag,

Could mount. And if the precinct of this coast

Were not less ample than the last, for him

I know not, but my strength had surely fail'd.

But Malebolge all toward the mouth

Inclining of the nethermost abyss,

The site of every valley hence requires,

That one side upward slope, the other fall.

At length the point of our descent we reach'd

From the last flag: soon as to that arriv'd,

So was the breath exhausted from my lungs,

I could no further, but did seat me there.

"Now needs thy best of man;" so spake my guide:

"For not on downy plumes, nor under shade

Of canopy reposing, fame is won,

Without which whosoe'er consumes his days

Leaveth such vestige of himself on earth,

As smoke in air or foam upon the wave.

Thou therefore rise: vanish thy weariness

By the mind's effort, in each struggle form'd

To vanquish, if she suffer not the weight

Of her corporeal frame to crush her down.

A longer ladder yet remains to scale.

From these to have escap'd sufficeth not.

If well thou note me, profit by my words."

I straightway rose, and show'd myself less spent

Than I in truth did feel me. "On," I cried,

"For I am stout and fearless." Up the rock

Our way we held, more rugged than before,

Narrower and steeper far to climb. From talk

I ceas'd not, as we journey'd, so to seem

Least faint; whereat a voice from the other foss

Did issue forth, for utt'rance suited ill.

Though on the arch that crosses there I stood,

What were the words I knew not, but who spake

Seem'd mov'd in anger. Down I stoop'd to look,

But my quick eye might reach not to the depth

For shrouding darkness; wherefore thus I spake:

"To the next circle, Teacher, bend thy steps,

And from the wall dismount we; for as hence

I hear and understand not, so I see

Beneath, and naught discern."—"I answer not,"

Said he, "but by the deed. To fair request

Silent performance maketh best return."

We from the bridge's head descended, where

To the eighth mound it joins, and then the chasm

Opening to view, I saw a crowd within

Of serpents terrible, so strange of shape

And hideous, that remembrance in my veins

Yet shrinks the vital current. Of her sands

Let Lybia vaunt no more: if Jaculus,

Pareas and Chelyder be her brood,

Cenchris and Amphisboena, plagues so dire

Or in such numbers swarming ne'er she shew'd,

Not with all Ethiopia, and whate'er

Above the Erythraean sea is spawn'd.

Amid this dread exuberance of woe

Ran naked spirits wing'd with horrid fear,

Nor hope had they of crevice where to hide,

Or heliotrope to charm them out of view.

With serpents were their hands behind them bound,

Which through their reins infix'd the tail and head

Twisted in folds before. And lo! on one

Near to our side, darted an adder up,

And, where the neck is on the shoulders tied,

Transpierc'd him. Far more quickly than e'er pen

Wrote O or I, he kindled, burn'd, and chang'd

To ashes, all pour'd out upon the earth.

When there dissolv'd he lay, the dust again

Uproll'd spontaneous, and the self-same form

Instant resumed. So mighty sages tell,

The' Arabian Phoenix, when five hundred years

Have well nigh circled, dies, and springs forthwith

Renascent. Blade nor herb throughout his life

He tastes, but tears of frankincense alone

And odorous amomum: swaths of nard

And myrrh his funeral shroud. As one that falls,

He knows not how, by force demoniac dragg'd

To earth, or through obstruction fettering up

In chains invisible the powers of man,

Who, risen from his trance, gazeth around,

Bewilder'd with the monstrous agony

He hath endur'd, and wildly staring sighs;

So stood aghast the sinner when he rose.

Oh! how severe God's judgment, that deals out

Such blows in stormy vengeance! Who he was

My teacher next inquir'd, and thus in few

He answer'd: "Vanni Fucci am I call'd,

Not long since rained down from Tuscany

To this dire gullet. Me the beastial life

And not the human pleas'd, mule that I was,

Who in Pistoia found my worthy den."

I then to Virgil: "Bid him stir not hence,

And ask what crime did thrust him hither: once

A man I knew him choleric and bloody."

The sinner heard and feign'd not, but towards me

His mind directing and his face, wherein

Was dismal shame depictur'd, thus he spake:

"It grieves me more to have been caught by thee

In this sad plight, which thou beholdest, than

When I was taken from the other life.

I have no power permitted to deny

What thou inquirest." I am doom'd thus low

To dwell, for that the sacristy by me

Was rifled of its goodly ornaments,

And with the guilt another falsely charged.

But that thou mayst not joy to see me thus,

So as thou e'er shalt 'scape this darksome realm

Open thine ears and hear what I forebode.

Reft of the Neri first Pistoia pines,

Then Florence changeth citizens and laws.

From Valdimagra, drawn by wrathful Mars,

A vapour rises, wrapt in turbid mists,

And sharp and eager driveth on the storm

With arrowy hurtling o'er Piceno's field,

Whence suddenly the cloud shall burst, and strike

Each helpless Bianco prostrate to the ground.

This have I told, that grief may rend thy heart."

CANTO XXV

WHEN he had spoke, the sinner rais'd his hands

Pointed in mockery, and cried: "Take them, God!

I level them at thee!" From that day forth

The serpents were my friends; for round his neck

One of then rolling twisted, as it said,

"Be silent, tongue!" Another to his arms

Upgliding, tied them, riveting itself

So close, it took from them the power to move.

Pistoia! Ah Pistoia! why dost doubt

To turn thee into ashes, cumb'ring earth

No longer, since in evil act so far

Thou hast outdone thy seed? I did not mark,

Through all the gloomy circles of the' abyss,

Spirit, that swell'd so proudly 'gainst his God,

Not him, who headlong fell from Thebes. He fled,

Nor utter'd more; and after him there came

A centaur full of fury, shouting, "Where

Where is the caitiff?" On Maremma's marsh

Swarm not the serpent tribe, as on his haunch

They swarm'd, to where the human face begins.

Behind his head upon the shoulders lay,

With open wings, a dragon breathing fire

On whomsoe'er he met. To me my guide:

"Cacus is this, who underneath the rock

Of Aventine spread oft a lake of blood.

He, from his brethren parted, here must tread

A different journey, for his fraudful theft

Of the great herd, that near him stall'd; whence found

His felon deeds their end, beneath the mace

Of stout Alcides, that perchance laid on

A hundred blows, and not the tenth was felt."

While yet he spake, the centaur sped away:

And under us three spirits came, of whom

Nor I nor he was ware, till they exclaim'd;

"Say who are ye?" We then brake off discourse,

Intent on these alone. I knew them not;

But, as it chanceth oft, befell, that one

Had need to name another. "Where," said he,

"Doth Cianfa lurk?" I, for a sign my guide

Should stand attentive, plac'd against my lips

The finger lifted. If, O reader! now

Thou be not apt to credit what I tell,

No marvel; for myself do scarce allow

The witness of mine eyes. But as I looked

Toward them, lo! a serpent with six feet

Springs forth on one, and fastens full upon him:

His midmost grasp'd the belly, a forefoot

Seiz'd on each arm (while deep in either cheek

He flesh'd his fangs); the hinder on the thighs

Were spread, 'twixt which the tail inserted curl'd

Upon the reins behind. Ivy ne'er clasp'd

A dodder'd oak, as round the other's limbs

The hideous monster intertwin'd his own.

Then, as they both had been of burning wax,

Each melted into other, mingling hues,

That which was either now was seen no more.

Thus up the shrinking paper, ere it burns,

A brown tint glides, not turning yet to black,

And the clean white expires. The other two

Look'd on exclaiming: "Ah, how dost thou change,

Agnello! See! Thou art nor double now,

"Nor only one." The two heads now became

One, and two figures blended in one form

Appear'd, where both were lost. Of the four lengths

Two arms were made: the belly and the chest

The thighs and legs into such members chang'd,

As never eye hath seen. Of former shape

All trace was vanish'd. Two yet neither seem'd

That image miscreate, and so pass'd on

With tardy steps. As underneath the scourge

Of the fierce dog-star, that lays bare the fields,

Shifting from brake to brake, the lizard seems

A flash of lightning, if he thwart the road,

So toward th' entrails of the other two

Approaching seem'd, an adder all on fire,

As the dark pepper-grain, livid and swart.

In that part, whence our life is nourish'd first,

One he transpierc'd; then down before him fell

Stretch'd out. The pierced spirit look'd on him

But spake not; yea stood motionless and yawn'd,

As if by sleep or fev'rous fit assail'd.

He ey'd the serpent, and the serpent him.

One from the wound, the other from the mouth

Breath'd a thick smoke, whose vap'ry columns join'd.

Lucan in mute attention now may hear,

Nor thy disastrous fate, Sabellus! tell,

Nor shine, Nasidius! Ovid now be mute.

What if in warbling fiction he record

Cadmus and Arethusa, to a snake

Him chang'd, and her into a fountain clear,

I envy not; for never face to face

Two natures thus transmuted did he sing,

Wherein both shapes were ready to assume

The other's substance. They in mutual guise

So answer'd, that the serpent split his train

Divided to a fork, and the pierc'd spirit

Drew close his steps together, legs and thighs

Compacted, that no sign of juncture soon

Was visible: the tail disparted took

The figure which the spirit lost, its skin

Soft'ning, his indurated to a rind.

The shoulders next I mark'd, that ent'ring join'd

The monster's arm-pits, whose two shorter feet

So lengthen'd, as the other's dwindling shrunk.

The feet behind then twisting up became

That part that man conceals, which in the wretch

Was cleft in twain. While both the shadowy smoke

With a new colour veils, and generates

Th' excrescent pile on one, peeling it off

From th' other body, lo! upon his feet

One upright rose, and prone the other fell.

Not yet their glaring and malignant lamps

Were shifted, though each feature chang'd beneath.

Of him who stood erect, the mounting face

Retreated towards the temples, and what there

Superfluous matter came, shot out in ears

From the smooth cheeks, the rest, not backward dragg'd,

Of its excess did shape the nose; and swell'd

Into due size protuberant the lips.

He, on the earth who lay, meanwhile extends

His sharpen'd visage, and draws down the ears

Into the head, as doth the slug his horns.

His tongue continuous before and apt

For utt'rance, severs; and the other's fork

Closing unites. That done the smoke was laid.

The soul, transform'd into the brute, glides off,

Hissing along the vale, and after him

The other talking sputters; but soon turn'd

His new-grown shoulders on him, and in few

Thus to another spake: "Along this path

Crawling, as I have done, speed Buoso now!"

So saw I fluctuate in successive change

Th' unsteady ballast of the seventh hold:

And here if aught my tongue have swerv'd, events

So strange may be its warrant. O'er mine eyes

Confusion hung, and on my thoughts amaze.

Yet 'scap'd they not so covertly, but well

I mark'd Sciancato: he alone it was

Of the three first that came, who chang'd not: thou,

The other's fate, Gaville, still dost rue.

CANTO XXVI

FLORENCE exult! for thou so mightily

Hast thriven, that o'er land and sea thy wings

Thou beatest, and thy name spreads over hell!

Among the plund'rers such the three I found

Thy citizens, whence shame to me thy son,

And no proud honour to thyself redounds.

But if our minds, when dreaming near the dawn,

Are of the truth presageful, thou ere long

Shalt feel what Prato, (not to say the rest)

Would fain might come upon thee; and that chance

Were in good time, if it befell thee now.

Would so it were, since it must needs befall!

For as time wears me, I shall grieve the more.

We from the depth departed; and my guide

Remounting scal'd the flinty steps, which late

We downward trac'd, and drew me up the steep.

Pursuing thus our solitary way

Among the crags and splinters of the rock,

Sped not our feet without the help of hands.

Then sorrow seiz'd me, which e'en now revives,

As my thought turns again to what I saw,

And, more than I am wont, I rein and curb

The powers of nature in me, lest they run

Where Virtue guides not; that if aught of good

My gentle star, or something better gave me,

I envy not myself the precious boon.

As in that season, when the sun least veils

His face that lightens all, what time the fly

Gives way to the shrill gnat, the peasant then

Upon some cliff reclin'd, beneath him sees

Fire-flies innumerous spangling o'er the vale,

Vineyard or tilth, where his day-labour lies:

With flames so numberless throughout its space

Shone the eighth chasm, apparent, when the depth

Was to my view expos'd. As he, whose wrongs

The bears aveng'd, at its departure saw

Elijah's chariot, when the steeds erect

Rais'd their steep flight for heav'n; his eyes meanwhile,

Straining pursu'd them, till the flame alone

Upsoaring like a misty speck he kenn'd;

E'en thus along the gulf moves every flame,

A sinner so enfolded close in each,

That none exhibits token of the theft.

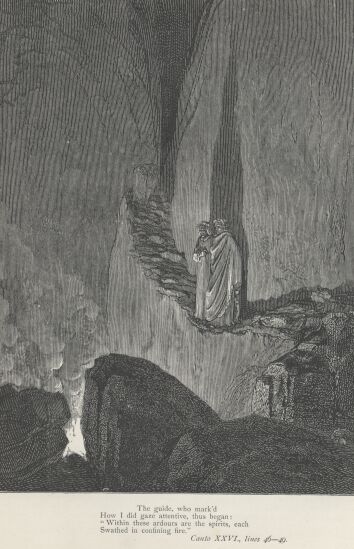

Upon the bridge I forward bent to look,

And grasp'd a flinty mass, or else had fall'n,

Though push'd not from the height. The guide, who mark'd

How I did gaze attentive, thus began:

"Within these ardours are the spirits, each

Swath'd in confining fire."—"Master, thy word,"

I answer'd, "hath assur'd me; yet I deem'd

Already of the truth, already wish'd

To ask thee, who is in yon fire, that comes

So parted at the summit, as it seem'd

Ascending from that funeral pile, where lay

The Theban brothers?" He replied: "Within

Ulysses there and Diomede endure

Their penal tortures, thus to vengeance now

Together hasting, as erewhile to wrath.

These in the flame with ceaseless groans deplore

The ambush of the horse, that open'd wide

A portal for that goodly seed to pass,

Which sow'd imperial Rome; nor less the guile

Lament they, whence of her Achilles 'reft

Deidamia yet in death complains.

And there is rued the stratagem, that Troy

Of her Palladium spoil'd."—"If they have power

Of utt'rance from within these sparks," said I,

"O master! think my prayer a thousand fold

In repetition urg'd, that thou vouchsafe

To pause, till here the horned flame arrive.

See, how toward it with desire I bend."

He thus: "Thy prayer is worthy of much praise,

And I accept it therefore: but do thou

Thy tongue refrain: to question them be mine,

For I divine thy wish: and they perchance,

For they were Greeks, might shun discourse with thee."

When there the flame had come, where time and place

Seem'd fitting to my guide, he thus began:

"O ye, who dwell two spirits in one fire!

If living I of you did merit aught,

Whate'er the measure were of that desert,

When in the world my lofty strain I pour'd,

Move ye not on, till one of you unfold

In what clime death o'ertook him self-destroy'd."

Of the old flame forthwith the greater horn

Began to roll, murmuring, as a fire

That labours with the wind, then to and fro

Wagging the top, as a tongue uttering sounds,

Threw out its voice, and spake: "When I escap'd

From Circe, who beyond a circling year

Had held me near Caieta, by her charms,

Ere thus Aeneas yet had nam'd the shore,

Nor fondness for my son, nor reverence

Of my old father, nor return of love,

That should have crown'd Penelope with joy,

Could overcome in me the zeal I had

T' explore the world, and search the ways of life,

Man's evil and his virtue. Forth I sail'd

Into the deep illimitable main,

With but one bark, and the small faithful band

That yet cleav'd to me. As Iberia far,

Far as Morocco either shore I saw,

And the Sardinian and each isle beside

Which round that ocean bathes. Tardy with age

Were I and my companions, when we came

To the strait pass, where Hercules ordain'd

The bound'ries not to be o'erstepp'd by man.

The walls of Seville to my right I left,

On the' other hand already Ceuta past.

"O brothers!" I began, "who to the west

Through perils without number now have reach'd,

To this the short remaining watch, that yet

Our senses have to wake, refuse not proof

Of the unpeopled world, following the track

Of Phoebus. Call to mind from whence we sprang:

Ye were not form'd to live the life of brutes

But virtue to pursue and knowledge high."

With these few words I sharpen'd for the voyage

The mind of my associates, that I then

Could scarcely have withheld them. To the dawn

Our poop we turn'd, and for the witless flight

Made our oars wings, still gaining on the left.

Each star of the' other pole night now beheld,

And ours so low, that from the ocean-floor

It rose not. Five times re-illum'd, as oft

Vanish'd the light from underneath the moon

Since the deep way we enter'd, when from far

Appear'd a mountain dim, loftiest methought

Of all I e'er beheld. Joy seiz'd us straight,

But soon to mourning changed. From the new land

A whirlwind sprung, and at her foremost side

Did strike the vessel. Thrice it whirl'd her round

With all the waves, the fourth time lifted up

The poop, and sank the prow: so fate decreed:

And over us the booming billow clos'd."

CANTO XVII

NOW upward rose the flame, and still'd its light

To speak no more, and now pass'd on with leave

From the mild poet gain'd, when following came

Another, from whose top a sound confus'd,

Forth issuing, drew our eyes that way to look.

As the Sicilian bull, that rightfully

His cries first echoed, who had shap'd its mould,

Did so rebellow, with the voice of him

Tormented, that the brazen monster seem'd

Pierc'd through with pain; thus while no way they found

Nor avenue immediate through the flame,

Into its language turn'd the dismal words:

But soon as they had won their passage forth,

Up from the point, which vibrating obey'd

Their motion at the tongue, these sounds we heard:

"O thou! to whom I now direct my voice!

That lately didst exclaim in Lombard phrase,

'Depart thou, I solicit thee no more,'

Though somewhat tardy I perchance arrive

Let it not irk thee here to pause awhile,

And with me parley: lo! it irks not me

And yet I burn. If but e'en now thou fall

into this blind world, from that pleasant land

Of Latium, whence I draw my sum of guilt,

Tell me if those, who in Romagna dwell,

Have peace or war. For of the mountains there

Was I, betwixt Urbino and the height,

Whence Tyber first unlocks his mighty flood."

Leaning I listen'd yet with heedful ear,

When, as he touch'd my side, the leader thus:

"Speak thou: he is a Latian." My reply

Was ready, and I spake without delay:

"O spirit! who art hidden here below!

Never was thy Romagna without war

In her proud tyrants' bosoms, nor is now:

But open war there left I none. The state,

Ravenna hath maintain'd this many a year,

Is steadfast. There Polenta's eagle broods,

And in his broad circumference of plume

O'ershadows Cervia. The green talons grasp

The land, that stood erewhile the proof so long,

And pil'd in bloody heap the host of France.

"The' old mastiff of Verruchio and the young,

That tore Montagna in their wrath, still make,

Where they are wont, an augre of their fangs.

"Lamone's city and Santerno's range

Under the lion of the snowy lair.

Inconstant partisan! that changeth sides,

Or ever summer yields to winter's frost.

And she, whose flank is wash'd of Savio's wave,

As 'twixt the level and the steep she lies,

Lives so 'twixt tyrant power and liberty.

"Now tell us, I entreat thee, who art thou?

Be not more hard than others. In the world,

So may thy name still rear its forehead high."

Then roar'd awhile the fire, its sharpen'd point

On either side wav'd, and thus breath'd at last:

"If I did think, my answer were to one,

Who ever could return unto the world,

This flame should rest unshaken. But since ne'er,

If true be told me, any from this depth

Has found his upward way, I answer thee,

Nor fear lest infamy record the words.

"A man of arms at first, I cloth'd me then

In good Saint Francis' girdle, hoping so

T' have made amends. And certainly my hope

Had fail'd not, but that he, whom curses light on,

The' high priest again seduc'd me into sin.

And how and wherefore listen while I tell.

Long as this spirit mov'd the bones and pulp

My mother gave me, less my deeds bespake

The nature of the lion than the fox.

All ways of winding subtlety I knew,

And with such art conducted, that the sound

Reach'd the world's limit. Soon as to that part

Of life I found me come, when each behoves

To lower sails and gather in the lines;

That which before had pleased me then I rued,

And to repentance and confession turn'd;

Wretch that I was! and well it had bested me!

The chief of the new Pharisees meantime,

Waging his warfare near the Lateran,

Not with the Saracens or Jews (his foes

All Christians were, nor against Acre one

Had fought, nor traffic'd in the Soldan's land),

He his great charge nor sacred ministry

In himself, rev'renc'd, nor in me that cord,

Which us'd to mark with leanness whom it girded.

As in Socrate, Constantine besought

To cure his leprosy Sylvester's aid,

So me to cure the fever of his pride

This man besought: my counsel to that end

He ask'd: and I was silent: for his words

Seem'd drunken: but forthwith he thus resum'd:

"From thy heart banish fear: of all offence

I hitherto absolve thee. In return,

Teach me my purpose so to execute,

That Penestrino cumber earth no more.

Heav'n, as thou knowest, I have power to shut

And open: and the keys are therefore twain,

The which my predecessor meanly priz'd."

Then, yielding to the forceful arguments,

Of silence as more perilous I deem'd,

And answer'd: "Father! since thou washest me

Clear of that guilt wherein I now must fall,

Large promise with performance scant, be sure,

Shall make thee triumph in thy lofty seat."

"When I was number'd with the dead, then came

Saint Francis for me; but a cherub dark

He met, who cried: "'Wrong me not; he is mine,

And must below to join the wretched crew,

For the deceitful counsel which he gave.

E'er since I watch'd him, hov'ring at his hair,

No power can the impenitent absolve;

Nor to repent and will at once consist,

By contradiction absolute forbid."

Oh mis'ry! how I shook myself, when he

Seiz'd me, and cried, "Thou haply thought'st me not

A disputant in logic so exact."

To Minos down he bore me, and the judge

Twin'd eight times round his callous back the tail,

Which biting with excess of rage, he spake:

'This is a guilty soul, that in the fire

Must vanish.' Hence perdition-doom'd I rove

A prey to rankling sorrow in this garb."

When he had thus fulfill'd his words, the flame

In dolour parted, beating to and fro,

And writhing its sharp horn. We onward went,

I and my leader, up along the rock,

Far as another arch, that overhangs

The foss, wherein the penalty is paid

Of those, who load them with committed sin.

CANTO XXVIII

WHO, e'en in words unfetter'd, might at full

Tell of the wounds and blood that now I saw,

Though he repeated oft the tale? No tongue

So vast a theme could equal, speech and thought

Both impotent alike. If in one band

Collected, stood the people all, who e'er

Pour'd on Apulia's happy soil their blood,

Slain by the Trojans, and in that long war

When of the rings the measur'd booty made

A pile so high, as Rome's historian writes

Who errs not, with the multitude, that felt

The grinding force of Guiscard's Norman steel,

And those the rest, whose bones are gather'd yet

At Ceperano, there where treachery

Branded th' Apulian name, or where beyond

Thy walls, O Tagliacozzo, without arms

The old Alardo conquer'd; and his limbs

One were to show transpierc'd, another his

Clean lopt away; a spectacle like this

Were but a thing of nought, to the' hideous sight

Of the ninth chasm. A rundlet, that hath lost

Its middle or side stave, gapes not so wide,

As one I mark'd, torn from the chin throughout

Down to the hinder passage: 'twixt the legs

Dangling his entrails hung, the midriff lay

Open to view, and wretched ventricle,

That turns th' englutted aliment to dross.

Whilst eagerly I fix on him my gaze,

He ey'd me, with his hands laid his breast bare,

And cried; "Now mark how I do rip me! lo!

"How is Mohammed mangled! before me

Walks Ali weeping, from the chin his face

Cleft to the forelock; and the others all

Whom here thou seest, while they liv'd, did sow

Scandal and schism, and therefore thus are rent.

A fiend is here behind, who with his sword

Hacks us thus cruelly, slivering again

Each of this ream, when we have compast round

The dismal way, for first our gashes close

Ere we repass before him. But say who

Art thou, that standest musing on the rock,

Haply so lingering to delay the pain

Sentenc'd upon thy crimes?"—"Him death not yet,"

My guide rejoin'd, "hath overta'en, nor sin

Conducts to torment; but, that he may make

Full trial of your state, I who am dead

Must through the depths of hell, from orb to orb,

Conduct him. Trust my words, for they are true."

More than a hundred spirits, when that they heard,

Stood in the foss to mark me, through amazed,

Forgetful of their pangs. "Thou, who perchance

Shalt shortly view the sun, this warning thou

Bear to Dolcino: bid him, if he wish not

Here soon to follow me, that with good store

Of food he arm him, lest impris'ning snows

Yield him a victim to Novara's power,

No easy conquest else." With foot uprais'd

For stepping, spake Mohammed, on the ground

Then fix'd it to depart. Another shade,

Pierc'd in the throat, his nostrils mutilate

E'en from beneath the eyebrows, and one ear

Lopt off, who with the rest through wonder stood

Gazing, before the rest advanc'd, and bar'd

His wind-pipe, that without was all o'ersmear'd

With crimson stain. "O thou!" said 'he, "whom sin

Condemns not, and whom erst (unless too near

Resemblance do deceive me) I aloft

Have seen on Latian ground, call thou to mind

Piero of Medicina, if again

Returning, thou behold'st the pleasant land

That from Vercelli slopes to Mercabo;

"And there instruct the twain, whom Fano boasts

Her worthiest sons, Guido and Angelo,

That if 't is giv'n us here to scan aright

The future, they out of life's tenement

Shall be cast forth, and whelm'd under the waves

Near to Cattolica, through perfidy

Of a fell tyrant. 'Twixt the Cyprian isle

And Balearic, ne'er hath Neptune seen

An injury so foul, by pirates done

Or Argive crew of old. That one-ey'd traitor

(Whose realm there is a spirit here were fain

His eye had still lack'd sight of) them shall bring

To conf'rence with him, then so shape his end,

That they shall need not 'gainst Focara's wind

Offer up vow nor pray'r." I answering thus:

"Declare, as thou dost wish that I above

May carry tidings of thee, who is he,

In whom that sight doth wake such sad remembrance?"

Forthwith he laid his hand on the cheek-bone

Of one, his fellow-spirit, and his jaws

Expanding, cried: "Lo! this is he I wot of;

He speaks not for himself: the outcast this

Who overwhelm'd the doubt in Caesar's mind,

Affirming that delay to men prepar'd

Was ever harmful. "Oh how terrified

Methought was Curio, from whose throat was cut

The tongue, which spake that hardy word. Then one

Maim'd of each hand, uplifted in the gloom

The bleeding stumps, that they with gory spots

Sullied his face, and cried: 'Remember thee

Of Mosca, too, I who, alas! exclaim'd,

"The deed once done there is an end," that prov'd

A seed of sorrow to the Tuscan race."

I added: "Ay, and death to thine own tribe."

Whence heaping woe on woe he hurried off,

As one grief stung to madness. But I there

Still linger'd to behold the troop, and saw

Things, such as I may fear without more proof

To tell of, but that conscience makes me firm,

The boon companion, who her strong breast-plate

Buckles on him, that feels no guilt within

And bids him on and fear not. Without doubt

I saw, and yet it seems to pass before me,

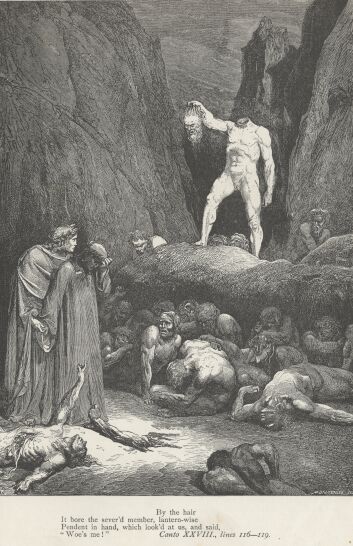

A headless trunk, that even as the rest

Of the sad flock pac'd onward. By the hair

It bore the sever'd member, lantern-wise

Pendent in hand, which look'd at us and said,

"Woe's me!" The spirit lighted thus himself,

And two there were in one, and one in two.

How that may be he knows who ordereth so.

When at the bridge's foot direct he stood,

His arm aloft he rear'd, thrusting the head

Full in our view, that nearer we might hear

The words, which thus it utter'd: "Now behold

This grievous torment, thou, who breathing go'st

To spy the dead; behold if any else

Be terrible as this. And that on earth

Thou mayst bear tidings of me, know that I

Am Bertrand, he of Born, who gave King John

The counsel mischievous. Father and son

I set at mutual war. For Absalom

And David more did not Ahitophel,

Spurring them on maliciously to strife.

For parting those so closely knit, my brain

Parted, alas! I carry from its source,

That in this trunk inhabits. Thus the law

Of retribution fiercely works in me."

|